(#89: 3 April 1971, 2 weeks)

Track listing: Home Lovin’ Man/Your Song/For The Good Times/Something/It’s Impossible/We’ve Only Just Begun/I Think I Love You/Candida/Fire And Rain/Rose Garden/My Sweet Lord

“…in the far hope of that happiness, I give life one more chance…”

(BS Johnson, Trawl)

It’s one of his most moving performances, perhaps because it’s so undemonstrative; both voice and music play hushed, as in the crypt, struck glad by the awe of unquestioned worship, a quiet church organ, bass drum as heartbeat four years ahead of “I’m Not In Love.” He is an old sea cap’n, coming back from maybe decades of sailing with no expressed intent; he knows he’ll miss the free-blown life but he’s missing something more, a home which may have changed beyond recognition throughout the time he’s been away.

As the song gradually opens up, we realise that he’s not the only one cognisant of the homecoming; his whole crew are approaching the dock, and there is a crowd waiting, their faces formerly “long and drawn,” now more exhausted than glad to see their other halves returning, for good – or perhaps there is some dread mixed in - never gave up hope? Are they home from the wars? And, if so, how many wars have they known, how many unspeakable darknesses have they witnessed? But the singer never overdoes anything; the chorus is almost whispered in closeted, or cloistered, harmonies. It is a song about coming home which skilfully avoids the question of what kind of home they are coming back to.

Perhaps there was a Vietnam subtext in there somewhere, but “Home Lovin’ Man,” the song, never played in the States; it was written specially for Williams by three of the period’s top British songwriters, Roger Cook, Roger Greenaway and Tony Macaulay, and was a substantial hit single in Britain (#7) over the Christmas of 1970. Moreover, it has scarcely surfaced in any form outside of Europe; Home Lovin’ Man, the album, does not exist outside Britain – there was in America an equivalent LP, Love Story, with an identical cover, typography and track listing, but with a different title track – “Where Do I Begin?,” one of Williams’ most drainingly passionate performances, was in our top ten while this album was at number one (there was a subsequent UK album entitled Love Story but this story can do without further tangles). Broadly speaking, however, Home Lovin’ Man is about someone, a little out of his own time, attempting to come to terms with the world, and the concept of “home,” which 1971 seemed to present to him.

Side one is largely agreeable listening; the sailor home from the sea attempting to re-establish relationships, or form new ones. “Your Song” was a very early recognition of Elton John, although the drift of Williams’ version is far gentler, less markedly troubled; the “sat on the roof” verse concerning itself with the mechanics of songwriting is omitted, and instead we are presented with a man – whose phrasing and general, intimidated reticence remind me, and not for the last time on this album, of George Michael – simply wanting to say how good it was to have another human being in this world, the electric piano acting as his destined featherbed.

He tries one-night stands, but these don’t work either; Kris Kristofferson’s “For The Good Times” is the sober sequel to “Help Me Make It Through The Night” – OK, so it’s morning, now what do we do, with the shrugged shoulders, paused cigarette puffs, polite dressings which that sort of thing entails – and Williams pitches the song as though wanting to go back to sleep, possibly forever; the glockenspiel represents the raindrops, the close harmonies, trumpet and strings seek to soothe a wrecked soul. Whereas Perry Como’s more famous version two years hence has an air of resigned regret honed by years of hurting experience, Williams sounds genuinely heartbroken; by the time the song fades, he disappears into the mirrors of his own indistinct murmurs.

The song’s harmonies are subtly simplified – anything to null the pain which he can’t quite pin down; after all, isn’t he back at home, where he had always wanted to be? – as are those of “Something.” Artie Butler’s arrangement is surprisingly reminiscent of Oliver Nelson (cf. “Stolen Moments”) or the Gil Evans of “Bilbao Song,” but Williams is still searching to identify what that “something” is supposed to be; the final “know” of his “I don’t know”s in the second middle eight vanishes into a vertiginous pond of echo, and the whole song seems to sidle to a halt before reluctantly starting up again. Williams’ voice works up to a high C which hangs on like the last feather of a chaffinch trying to avoid the eagle’s talons. In his careful, tranced humming of the song's central melody line, however, he is at least striving for a peace.

“It’s Impossible,” Perry Como’s big comeback hit of the period, begins, like most of these tracks, with an intimation of wanting to be “Wichita Lineman” – that definitive song about being as far from home, or humanity, as possible – but Williams’ reading is far more intimate. The “cosy, laidback hipness” of the 1971 lounge is intact – these are Lena’s words, and she detected a kinship with late period Stereolab (e.g. Cobra And Phases Group Play Voltage In The Milky Night) in Butler’s charts. Still, even in this expression of hangdog happiness, Williams sounds troubled; his extended “soul” in the second “sell my very soul” makes you wonder whether he will, indeed, regret selling it, and Butler’s deliberately ambiguous harmonic ending to the song is a marked, stark contrast to the happy end credits of Como’s version.

But Williams rallies, realises that this is now his life, and his “We’ve Only Just Begun,” despite the sitar, buckles with regained confidence. The choral arrangement is aptly airy, the “fly”s as free as the Free Design. Then, via another moment of suspended animation – which way will he turn? What will he decide? – the bass leads a settling down into evening; the lights dim, Keith Mansfield’s “Life Of Leisure” appears on the horizon, and, rolling up a key, Williams finally approaches, and embraces, comfort and contentment. Home – it’s the place we’ve all been aiming for, and he is now there, reached, retrieved, saved.

Or is he? Side two indicates that the stir might be driving him a little crazy. “I Think I Love You” has to be sung by a panting, self-doubting, barely out of puberty David Cassidy; despite Butler’s inventive touches – the clavinet burps and bass clarinet farts underscoring the middle eight – Williams sounds, all of a sudden, clumsy, clinging, something less than reassuring. The situation scarcely changes with his redundant reading of Dawn’s odious “Candida”; although not approaching, or descending to, Tony Orlando’s dirty old neighbour persona, there is little Williams can do to redeem such a ridiculous song (“The-eee first pri-iiiize,” the girl next door reduced to fairground attraction level), and his attempts are nevertheless buried by the “Young New Mexican Puppeteer” trumpets. Williams isn’t playing “happy” very well.

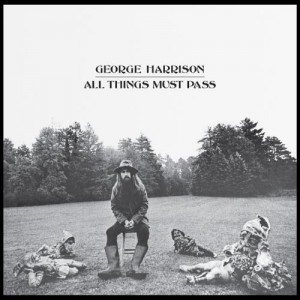

But then, and to his credit, he feels the need for emotional adventure. James Taylor’s “Fire And Rain” is a huge risk for any would-be interpreter, the song itself being so discomfortingly personal, with its references to suicides and electric shock treatment, but if not quite at the Bobby Womack level, Williams does not disgrace himself; instead, we are presented with a picture of a home-come man who remains stranded, landlocked – “But I always thought that I’d see you again”; this is the place that I left all those years ago – isn’t it? Where is everybody? Where have they all gone? Meanwhile, you don’t know the half of what I’ve seen, having been so utterly at sea for so long – but who is there left for me to tell the tale to? Sweet Baby James, a major album – although the record never placed higher than #6 on our chart, it stayed there for a year and infected everybody – considered Taylor’s standing, as a musician and as a human being, as his and everyone else’s old world was seen to have become lost. Like Harrison, lost in his garden and his castle, Williams has indeed come home – but it’s not what he expected, not really what he wanted, and he tries his best to recognise his surroundings, his people, but it’s becoming more and more of a struggle. With “Rose Garden” he takes Joe South’s homilies firmly into the lounge, though with only one verse intact, and with the inescapable undertow of Jobim (and Claus Ogerman in Butler’s arrangement), this is more of a meditation on the song, even on the notion of “song.” Why can’t everything be perfect? Well, there’s rain and it comes with the sun, you know the deal…

Finally, and quite astoundingly, he finds himself in exactly the same place as Harrison. The A-list studio players do their best to replicate the bear-like whine of Harrison’s slides but Williams is already looking for something beyond “home”; he sounds immensely concentrated, and convinced, here. He takes his time, waiting for the vision to unfold, and as the drums appear over the horizon and the Choir of the Wee Kirk o’ the Valley, Reseda, California, materialise to provide the hallelujahs, his soul, his commitment, becomes steadily more and more intense. The tension lies in whether the choir will go for the Krishnas, and eventually, after an elongated tease, they do; the song, the belief, gathers in spirit and radiance, its landed sailor now knowing that to come home isn’t in itself enough, that, unlike Johnson’s trawler tourist, who, seeing Ginnie waiting for him on the midnight quay, decides more in desperation than joy that he’ll give life one more chance, he has to rebuild his home, has to rediscover and reanimate all those things he once threw in the ocean. To love his home, he has to relearn the art of loving himself.

Track listing: Home Lovin’ Man/Your Song/For The Good Times/Something/It’s Impossible/We’ve Only Just Begun/I Think I Love You/Candida/Fire And Rain/Rose Garden/My Sweet Lord

“…in the far hope of that happiness, I give life one more chance…”

(BS Johnson, Trawl)

It’s one of his most moving performances, perhaps because it’s so undemonstrative; both voice and music play hushed, as in the crypt, struck glad by the awe of unquestioned worship, a quiet church organ, bass drum as heartbeat four years ahead of “I’m Not In Love.” He is an old sea cap’n, coming back from maybe decades of sailing with no expressed intent; he knows he’ll miss the free-blown life but he’s missing something more, a home which may have changed beyond recognition throughout the time he’s been away.

As the song gradually opens up, we realise that he’s not the only one cognisant of the homecoming; his whole crew are approaching the dock, and there is a crowd waiting, their faces formerly “long and drawn,” now more exhausted than glad to see their other halves returning, for good – or perhaps there is some dread mixed in - never gave up hope? Are they home from the wars? And, if so, how many wars have they known, how many unspeakable darknesses have they witnessed? But the singer never overdoes anything; the chorus is almost whispered in closeted, or cloistered, harmonies. It is a song about coming home which skilfully avoids the question of what kind of home they are coming back to.

Perhaps there was a Vietnam subtext in there somewhere, but “Home Lovin’ Man,” the song, never played in the States; it was written specially for Williams by three of the period’s top British songwriters, Roger Cook, Roger Greenaway and Tony Macaulay, and was a substantial hit single in Britain (#7) over the Christmas of 1970. Moreover, it has scarcely surfaced in any form outside of Europe; Home Lovin’ Man, the album, does not exist outside Britain – there was in America an equivalent LP, Love Story, with an identical cover, typography and track listing, but with a different title track – “Where Do I Begin?,” one of Williams’ most drainingly passionate performances, was in our top ten while this album was at number one (there was a subsequent UK album entitled Love Story but this story can do without further tangles). Broadly speaking, however, Home Lovin’ Man is about someone, a little out of his own time, attempting to come to terms with the world, and the concept of “home,” which 1971 seemed to present to him.

Side one is largely agreeable listening; the sailor home from the sea attempting to re-establish relationships, or form new ones. “Your Song” was a very early recognition of Elton John, although the drift of Williams’ version is far gentler, less markedly troubled; the “sat on the roof” verse concerning itself with the mechanics of songwriting is omitted, and instead we are presented with a man – whose phrasing and general, intimidated reticence remind me, and not for the last time on this album, of George Michael – simply wanting to say how good it was to have another human being in this world, the electric piano acting as his destined featherbed.

He tries one-night stands, but these don’t work either; Kris Kristofferson’s “For The Good Times” is the sober sequel to “Help Me Make It Through The Night” – OK, so it’s morning, now what do we do, with the shrugged shoulders, paused cigarette puffs, polite dressings which that sort of thing entails – and Williams pitches the song as though wanting to go back to sleep, possibly forever; the glockenspiel represents the raindrops, the close harmonies, trumpet and strings seek to soothe a wrecked soul. Whereas Perry Como’s more famous version two years hence has an air of resigned regret honed by years of hurting experience, Williams sounds genuinely heartbroken; by the time the song fades, he disappears into the mirrors of his own indistinct murmurs.

The song’s harmonies are subtly simplified – anything to null the pain which he can’t quite pin down; after all, isn’t he back at home, where he had always wanted to be? – as are those of “Something.” Artie Butler’s arrangement is surprisingly reminiscent of Oliver Nelson (cf. “Stolen Moments”) or the Gil Evans of “Bilbao Song,” but Williams is still searching to identify what that “something” is supposed to be; the final “know” of his “I don’t know”s in the second middle eight vanishes into a vertiginous pond of echo, and the whole song seems to sidle to a halt before reluctantly starting up again. Williams’ voice works up to a high C which hangs on like the last feather of a chaffinch trying to avoid the eagle’s talons. In his careful, tranced humming of the song's central melody line, however, he is at least striving for a peace.

“It’s Impossible,” Perry Como’s big comeback hit of the period, begins, like most of these tracks, with an intimation of wanting to be “Wichita Lineman” – that definitive song about being as far from home, or humanity, as possible – but Williams’ reading is far more intimate. The “cosy, laidback hipness” of the 1971 lounge is intact – these are Lena’s words, and she detected a kinship with late period Stereolab (e.g. Cobra And Phases Group Play Voltage In The Milky Night) in Butler’s charts. Still, even in this expression of hangdog happiness, Williams sounds troubled; his extended “soul” in the second “sell my very soul” makes you wonder whether he will, indeed, regret selling it, and Butler’s deliberately ambiguous harmonic ending to the song is a marked, stark contrast to the happy end credits of Como’s version.

But Williams rallies, realises that this is now his life, and his “We’ve Only Just Begun,” despite the sitar, buckles with regained confidence. The choral arrangement is aptly airy, the “fly”s as free as the Free Design. Then, via another moment of suspended animation – which way will he turn? What will he decide? – the bass leads a settling down into evening; the lights dim, Keith Mansfield’s “Life Of Leisure” appears on the horizon, and, rolling up a key, Williams finally approaches, and embraces, comfort and contentment. Home – it’s the place we’ve all been aiming for, and he is now there, reached, retrieved, saved.

Or is he? Side two indicates that the stir might be driving him a little crazy. “I Think I Love You” has to be sung by a panting, self-doubting, barely out of puberty David Cassidy; despite Butler’s inventive touches – the clavinet burps and bass clarinet farts underscoring the middle eight – Williams sounds, all of a sudden, clumsy, clinging, something less than reassuring. The situation scarcely changes with his redundant reading of Dawn’s odious “Candida”; although not approaching, or descending to, Tony Orlando’s dirty old neighbour persona, there is little Williams can do to redeem such a ridiculous song (“The-eee first pri-iiiize,” the girl next door reduced to fairground attraction level), and his attempts are nevertheless buried by the “Young New Mexican Puppeteer” trumpets. Williams isn’t playing “happy” very well.

But then, and to his credit, he feels the need for emotional adventure. James Taylor’s “Fire And Rain” is a huge risk for any would-be interpreter, the song itself being so discomfortingly personal, with its references to suicides and electric shock treatment, but if not quite at the Bobby Womack level, Williams does not disgrace himself; instead, we are presented with a picture of a home-come man who remains stranded, landlocked – “But I always thought that I’d see you again”; this is the place that I left all those years ago – isn’t it? Where is everybody? Where have they all gone? Meanwhile, you don’t know the half of what I’ve seen, having been so utterly at sea for so long – but who is there left for me to tell the tale to? Sweet Baby James, a major album – although the record never placed higher than #6 on our chart, it stayed there for a year and infected everybody – considered Taylor’s standing, as a musician and as a human being, as his and everyone else’s old world was seen to have become lost. Like Harrison, lost in his garden and his castle, Williams has indeed come home – but it’s not what he expected, not really what he wanted, and he tries his best to recognise his surroundings, his people, but it’s becoming more and more of a struggle. With “Rose Garden” he takes Joe South’s homilies firmly into the lounge, though with only one verse intact, and with the inescapable undertow of Jobim (and Claus Ogerman in Butler’s arrangement), this is more of a meditation on the song, even on the notion of “song.” Why can’t everything be perfect? Well, there’s rain and it comes with the sun, you know the deal…

Finally, and quite astoundingly, he finds himself in exactly the same place as Harrison. The A-list studio players do their best to replicate the bear-like whine of Harrison’s slides but Williams is already looking for something beyond “home”; he sounds immensely concentrated, and convinced, here. He takes his time, waiting for the vision to unfold, and as the drums appear over the horizon and the Choir of the Wee Kirk o’ the Valley, Reseda, California, materialise to provide the hallelujahs, his soul, his commitment, becomes steadily more and more intense. The tension lies in whether the choir will go for the Krishnas, and eventually, after an elongated tease, they do; the song, the belief, gathers in spirit and radiance, its landed sailor now knowing that to come home isn’t in itself enough, that, unlike Johnson’s trawler tourist, who, seeing Ginnie waiting for him on the midnight quay, decides more in desperation than joy that he’ll give life one more chance, he has to rebuild his home, has to rediscover and reanimate all those things he once threw in the ocean. To love his home, he has to relearn the art of loving himself.