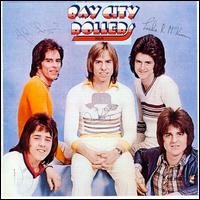

(#150: 8 February 1975, 3 weeks)

Track listing: Release Me/Quando Quando Quando/Les Bicyclettes De Belsize/Spanish Eyes/Am I That Easy To Forget/There Goes My Everything/A Man Without Love/Another Time, Another Place/Love Me With All Your Heart/The Way It Used To Be/Winter World Of Love/The Last Waltz

There is a famous photograph from 1967 which features Engelbert Humperdinck and Tom Jones, Decca and the year’s golden boys, lounging back, grinning, against their respective Rolls Royces, as if in affable disbelief – how come they haven’t rumbled us yet? Or, more precisely, the Likely Lads of post-Beatles British balladry, or, more floridly (according to the late Billy MacKenzie) “Thunderbirds in pop.”

For a while, to the public, they were inseparable – hanging out together, appearing on each other’s TV shows – and must have seemed like two sides of the same coin. These days, though, I think of Humperdinck as a kind of Pacino to Jones’ de Niro; the two styles need each other but Jones’ persona is the less trustworthy, the more evasive – he is able to scurry under his varying masks of toughness and roughness, stutters and mumbles in his songs, gives the impression he’s always two further corners round the corner than you might find comfortable. Whereas Humperdinck wouldn’t have a heart if he didn’t wear it on his sleeve; he is painfully conscious about setting his own record straight (as a singer) – Jones laughs or hiccups off sorrow and suffering, but Humperdinck thrusts his loneliness in our faces.

And lonely he was fated to be, just like Gene Pitney and George Michael (two other singers whose audiences have not taken well to finding happy – look at the top row of photos on the rear of His Greatest Hits, taken, as with the star shots for Elton John’s Greatest Hits, by Terry O’Neill, and you’d swear it was George circa 1985); it was for a time his oxygen, his lifeline. Never forget that when “Release Me” blasted off from the bottom of the bill at Sunday Night At The London Palladium and into the world, he was already thirty with nearly a decade of failure behind him; sometime nightclub performer, both as singer and saxophonist, he had been laid low for a fatal while by TB, and by the time Gordon Mills proposed the name change from Arnold (“Gerry”) Dorsey he was struggling to support his wife in a cold, bare flat in Hammersmith. This was his last roll of the dice; if “Engelbert” didn’t work, it would be proper job time.

But it did work, and not necessarily in the venerable “you’re too beautiful to suffer” trope of pop idolatry; there was that Anglo-Indian unplaceable exoticism about him – more pronounced than that other Anglo-Indian re-import, Cliff Richard – and the idea that he popped out from nowhere and seemed to come from everywhere provided sufficient allure for the demographic Lena has elsewhere termed “the Housewives of Valium Court”; left alone by their day job husbands to dream of other and better things. In his palpable suffering, he provided a relief projection screen for the pains of his audience.

Not that Humperdinck has ever been a tortured soul, or at least not in ways he has decided to divulge to us; he is generally self-deprecating, amiable, wears “vain” like a Better Badge. When hustled onto a package tour in early ’67 with Hendrix’ Experience and the Walker Brothers he surprisingly bonded with Jimi, who would study his act closely from the wings and to whom the older man would offer tips on how to work an audience. Once he even provided understudy guitar for Humperdinck (“You can’t do this, Jimi! You’re a star!” “Oh don’t worry, I’ll stand behind that curtain and nobody will know it’s me”), who remarked (approvingly) that it was like being backed by three guitars. In more recent times he has happily provided the vocal for “Lesbian Seagull,” and upon discovering Damon Albarn had asked him to participate in Gorillaz’ Plastic Beach and that his management had turned Albarn down flat, an appalled Humperdinck promptly dismissed the team and installed his son as manager.

It’s a remarkable story in many ways, but it’s all the sadder that, despite the Pacino comparison, Humperdinck had for the most part to deal with the equivalent of – Val Guest, or Gerald Thomas. The arrangers who contribute to these twelve songs are none of them awful as such – on the contrary, they include top names of the period such as ex-Joe Meek conspirator Charles Blackwell, Johnny Harris and Mike Vickers – but none seems to have been inspired to provide more than the obvious. Too many of these songs follow an identical formula, with tinkling piano, obligatory key changes for the final verse (to show off Humperdinck’s range) and, worst of all, a horribly obtrusive Light Programme choir who seem intent on pushing the singer towards heaven, or hell, as quickly as possible. You can tell why something like “Am I That Easy To Forget?” didn’t do quite as well as his ’67 trilogy of hits; the Horlicks singers are blocking Humperdinck’s emotional path, the watching-as-she-walks-out-on-me scenario too familiar; the formula was becoming tired.

Those ’67 trilogy of hits, however, the three biggest selling singles of a year which supposedly opposed all that these songs stood for; if anything, quite apart from providing some sort of reassurance to maturing screamers finding Revolver a bit much, these performances solidify and refract their inbuilt misery. “Release Me” was built on the template of Little Esther Phillips’ 1962 version, but holds none of the knowing sass of the impetuous and bored fourteen-year-old girl playing patient emotional table tennis with her backing singers. And just because Phillips’ version is the more “approachable” or “authentic” (in relation to what?) does not necessarily make hers the superior reading. Humperdinck captures his own mounting desperation very effectively, starting low and gradually building up to the point where, when he finally reaches the top C of the final “So,” he can barely balance himself. It is almost like a plea from the future to the past to let it escape, and live, and maybe has more in common with “Strawberry Fields Forever” than it cares to admit. In a nation where no-strings divorce had not yet quite been legalised, this cut through to a lot of disappointed hearts, and the single remained on the chart for well over a year (in part bolstered by its ebullient B-side “Ten Guitars” which latter sadly does not appear on this compilation). At least in “Release Me” he has another (and realer) love to go to, or go off with, but the two follow-ups cut off these escape routes. “There Goes My Everything” is enhanced by John McLaughlin’s imaginative guitar comping but cannot be taken seriously due to a bumptious bass trombone which plods through the arrangement like a doped elephant, let alone the “there goes my only possession” leitmotif (is he waiting for the repo men to come and pick her up?). With “The Last Waltz” there is little left save piano, and echoes (both oddly reminding me of Ultravox’s “Vienna”) and the trail of the song is anyway confusing; in its tenure he appears to meet the girl and finish with her in the space of two minutes. Muscially, too, Les Reed achieves a crafty fusion of new and old; the verses are a competent Bacharach pastiche but the chorus could have come out of Victorian operetta. But it doesn’t seem to presage anything approaching a desirable future.

Even when Humperdinck is “happy” there is always a sting in his wink. “Quando Quando Quando,” one of his most popular tracks (though a surprisingly under-performing single in the UK) and certainly one which I heard in my youth performed by endless Italian wedding bands, does well with Harris’ criss-crossing vertigos of strings and woodwind, but he hasn’t won her yet and it’s debatable whether he will. His “Spanish Eyes” is also less assured (and wobblier on the diction front) than Al Martino’s hit version, and brings out some of the song’s innate absurdities (suddenly they’re in Mexico! Say “si si”!). Still, we recall that in The Good Life, when Paul Eddington’s henpecked executive Jerry is having a rare afternoon off, he stretches himself out on the sofa, pours out some liquor and revels in a Humperdinck album; here is also the man many men of their time wished they could be.

The loneliness, meanwhile, gets worse. If not tackling Les Reed/Barry Mason originals, he’d most often be found reworking translated Italian San Remo weepies. Thus “A Man Without Love” strolls merrily on its ground of sprightly acoustic guitar, French horn, harp and accordion, such that we hardly notice what he’s singing: “I cannot face this world/That’s fallen down on me.” Like David Ruffin in “I Wish It Would Rain,” he cannot even leave his room. He even cites “If You Go Away” (“slowly dying”). “Les Bicyclettes De Belsize,” written by Reed and Mason for a scatty short film about a bloke on his bike and a billboard model who comes to life, tries to breathe carefree but again and again the mourning chords (and muted trumpets) drag it down. “Come the dawn,” concludes Huperdinck, “they are all dead – yes, they’re dead.” We could almost be listening to Scott 3.

1969’s “The Way It Used To Be” is possibly Humperdinck’s most tortured record, in that Mike Vickers’ orchestra and chorus seem to pummel into his head – there he is, out of his room, but he’s in the dark corner of a restaurant, on his own, and everyone and everything else in there seems to be laughing at him, ganging up on him. As with Herman’s Hermits’ contemporaneous “My Sentimental Friend,” he asks the band to strike up an old love song, in the meagre hope that “she” might be passing by and look in, and be changed “even if the words are not so tender.” His mirthless laugh of “Ha!” is bitter, and the song tries very hard not to be “You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me” (“It’s quite easy to let go/Then the song begins again”). Note the “crowded room” appearing yet again, like a harsh reminder of earlier and better times.

Reed’s arrangement of his and Mason’s “Winter World Of Love” does show some imagination, progressing from the icy “Il Silenzio” trumpet at the beginning to the hearth rug of Home Service strings which end the song, with Humperdinck progressively modifying his “O-ho”s to “Oh no” – but are they really going to stay in their bunker “until summer comes again” (well, it is the end of the sixties)?

As the seventies rolled around the Brtish hits began to dry up, although Humperdinck’s personal popularity did not and, if anything, increased abroad, especially in the States; 1970’s “Love Me With All My Heart,” a variation on “Love Is A Many Splendoured Thing,” did no business in the UK (there is a case for Humperdinck as inventor of X-Factor pop, with those bravura high notes, climactic key changes and choirs). His most interesting record of this period was 1971’s “Another Time, Another Place,” written by Mike Leander and Eddie Seago, which with its whirlybird arrangement is almost the anti-“Quando Quando Quando”; here is perhaps Humperdinck’s greatest torture – he keeps running into his ex no matter where he goes, and it’s always friendly and she’s almost always with somebody else – but the Strictly Come Dancing flourishes of Laurie Holloway’s aptly garish arrangement serve to mask deeper pains (“And I try desperately to hide”). Occasionally he even breaks into proto-Martin Fry mock-exasperation. And again, that word which keeps cropping up through the record, “regret.” Regret for not being hip, for sticking himself in , or to, the past?

But never, unlike Jones, does he do revenge songs. No, his is the epitome of pure romantic suffering; it’s a wonder that Mills didn’t think to rechristen him Heathcliff – it’s that intense and windblown. And that quality was still being clung to by a number of people, enough to get this last-ditch best-of to number one and on the chart for thirty-four weeks (last-ditch in that Humperdinck’s Decca contract was coming to an end, and so Decca took note of what K-Tel, Arcade and Ronco had been doing and advertised the record aggressively on TV; a signifier of a trend set to dominate the top of the album chart for the next fourteen years or so – single-artist retrospectives, and eventually the return of “Various Artists,” all aimed at relatively undiscriminating Woolworth’s buyers). But things were changing; Humperdinck, realising it was all finally rather ridiculous, if admirably so, ensconced himself happily on the Vegas circuit (and went on to score many more hits everywhere except Britain), Barry Manilow was waiting round the corner, and this year of 1975 will end in a quite different place, with another exotically glamorous, reinvented man of uncertain pedigree. But here we start, with the way it used to be, and who would ever think of trading in those Rolls Royces or conspiratorial schoolboy winks?

.jpg)