(#162: 22 November 1975, 5 weeks; 10 January 1976, 1 week)

Track listing: Magic Moments/Caterina/Catch A Falling Star/I Know/When You Were Sweet 16/I Believe/Try To Remember/Love Makes The World Go Round/Prisoner Of Love/Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes/Hot Diggity/Round And Round/If I Loved You/Hello Young Lovers/Delaware/Moonglow/Killing Me Softly/More/Dear Hearts & Gentle People/I Love You & Don’t You Forget It/And I Love You So/For The Good Times/Close To You/Seattle/Tie A Yellow Ribbon/Walk Right Back/What Kind Of Fool Am I/Days Of Wine And Roses/Where Do I Begin/Without A Song/It’s Impossible/I Think Of You/If/We’ve Only Just Begun/I Want To Give/Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head/You Make Me Feel So Young/Temptation/The Way We Were/Sing

(Author’s Note: I am well aware that several reputable chart sources list this album as being entitled 40 Greatest Hits, but both the front and back cover and the labels on all four sides of my LP copy say 40 Greatest and thus this is how I am billing it. The back cover does inform me that “THIS EXCITING L.P. IS ALSO NOW AVAILABLE ON CASSETTE AND 8-TRACK,” but since I have not found a copy in either of these formats – I fear that sending a cheque or postal order for £3.99 plus 25p for postage and handling might prove futile – this will have to do. I note that the spine of the album credits the title as FORTY GREATEST, but the sane and practical mind has to draw the line somewhere. Track titles, though mostly incomplete and/or deficient in punctuation, are listed as they appear on the back cover for similar sanity-preserving reasons)

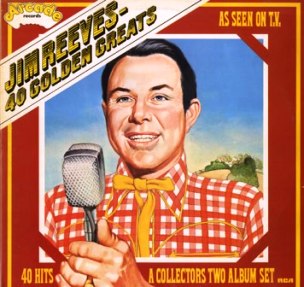

“Pleasant, easy, and a tad morose”; that’s Julie Powell in her book Cleaving, describing something else completely, but it was the phrase Lena remembered and applied to the voice and delivery of Perry Como. On balance this double package looks much more fun and attractive than the Jim Reeves one – K-Tel having presumably won the RCA licensing rights over Arcade – with a haiku-like biographical sleevenote written with commendable concision, plenty of photos from different eras of Como, and endorsements from celebrities of the calibre of Irving Berlin, Johnny Mercer, Mel Tormé and Gordon Jenkins; all still alive in 1975, and all relating to the singer’s impeccable technical standards and the elusive spark known as “warmth.” Warm enough to send this compilation under the Christmas trees of innumerable mothers over that Christmas.

So I naturally thought that a couple of hours in Como’s company would prove a lot less cumbersome than two hours of Jim Reeves. Not so. If anything I found these forty songs – in reality thirty-four, once you discount the six tracks pulled from Como’s previously discussed And I Love You So album – rather tougher going, and it has to be said that the prospect of slumber was only narrowly averted as, towards the end of the recital, Como sleepwalked through yet another neutralised seventies movie theme (“The Way We Were,” although my mind began to wander into abstraction somewhere in the midst of “We’ve Only Just Begun”). Indeed many of these tracks belie the common assumption of Como being the natural, easy-going, microphone-caressing successor to Bing Crosby, enough to make me wonder whether RCA ever really knew what to do with him, or whether he was content enough to deal with whatever RCA threw at him.

The question one has to ask is: what does this album tell us about Perry Como, both about his music and about him as a human being? The answer is a rather confused picture, but it is important to try to address it since Como is one of the biggest mysteries this tale is likely to come across. It would not be worth the time or effort of writers such as Kitty Kelley or Nick Tosches to delve into Como’s life, since it reveals absolutely no subtext and tells absolutely no stories. Sinatra and Martin had their empowering demons, but Como was a barber who one day found that he could sing and set to doing something about it; and when he became famous he preferred to remain out of the spotlight and devote himself to his family. He was married to the same woman for some sixty-five years; there is no dirt to be uncovered, no Crosby kin horror stories of domestic violence, a totally clean sheet, so clean as to be a blank. He did what he did and when he wasn’t doing it he was a caring and devout husband, father and grandfather, and sometimes he would slope off to play golf. His was a very WASP Eisenhower dream; and while a cynic might posit that he subscribed to many dullard right-wing beliefs, there is no concrete evidence to suggest anything other than what I see when I try to picture Como the family patriarch in my mind – namely Howard Cunningham from Happy Days, laidback, tolerant of his family’s misdemeanours, philosophical, fatalistic and, above all, amiable (politically I suspect him to have been a Republican of the Eisenhower type; moderate, hard-working, loyal to family and country, not even thinking that there was another way).

So perhaps that was the secret of Como’s appeal; an Everyman (if the term “Everyman” implies “averageness”), a nice, decent, ordinary guy, straight as a die, who happened to be able to sing his ass off and not even let you know that it was any kind of an effort, who sat down on stage in his rocking chair and/or wearing a sensible jumper like he’d just looked in from the front room. The kind of guy who could sing dumb novelty songs and searing ballads about the sun, the moon and the stars and make it all fit.

But the picture presented by 40 Greatest doesn’t quite fit, and maybe that’s because it’s incomplete. Although the album encompasses everything from his first recording (“Prisoner Of Love," from 1945) to his last hit (“I Want To Give”), many hits are missed out, and undue prominence given to Como’s seventies output; aside from the aforementioned And I Love You So, 1971’s It’s Impossible and 1974’s Perry albums are also generously sampled. Hence important records like “Papa Loves Mambo,” “Surrender,” “Wanted,” “Glendora,” “Ko Ko Mo” and others do not appear at all. What remains is a confused and confusing portrait of someone perhaps a little too nice and compliant for his own good, someone content that the industry should know what constitutes a “hit” and happy to go along with their suggestions.

With “Prisoner Of Love,” RCA looked to be searching for an alternative Mario Lanza. The song was already fourteen years old – and yes, it’s the same “Prisoner Of Love” subsequently attacked by James Brown – and plays like an overblown Victorian melodrama. Against the over-stuffed orchestration, Como has no option but to bellow the song as though it were the last act of Tosca; when his voice rises for emotional emphasis, it has a tendency to become strident. His essay on Carousel’s “If I Loved You” is also problematic since, despite a terrific vocal performance, he cannot breathe within the corset of the glutinous arrangement, which seems to hold no room for people. In addition, there is a running problem with this album in the form of obstinately intrusive backing singers; the early “When You Were Sweet 16” is a case in point – Como delivers a near-perfect out-of-tempo reading of the song, and it should have ended there; but no, here comes the celeste, and then the ghastly choir, to ruin the experience.

Como’s output into and through the fifties (and even unto the early sixties) suffered from the same kind of emotional schizophrenia. Essentially there is a split between goofy bits of nonsense like “Hot Diggity” and the repulsive “Delaware” (which latter unfortunately reminds me, musically, of an unwanted cross between the Horst Wessel song and “Ballad Of The Green Berets”) and more standard fare, like the sentimental but hopelessly dated waltz “More”; 1953’s transatlantic number one “Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes” whose essential lightness is undermined by barking Three Amigos backing vocals and snarling trombones; and 1958’s lunge at the rock ‘n’ roll market, “Love Makes The World Go Round,” a far bigger hit in the UK than in the US. Como despised rock ‘n’ roll and makes little effort to disguise his contempt in his vocal here, even resorting to sending up the “yay yay and a yay-YEAH!” backing vocals. Contempt? Actually he sounds as though he is falling asleep.

A better rapprochement with nowness was achieved in the historic 1958 double-sided smash “Magic Moments” – early Bacharach and David with jaunty whistling and bassoon, where the backing singers work with, rather than against, Como for a change (although the song and record are still really corny; “clutch down” to rhyme with “touchdown”?) - and the lovely “Catch A Falling Star,” with its “Spanish Harlem”-anticipating guitar (it suddenly rises in response to Como’s “tap you on the shoulder”) and subtler acknowledgements to rock ‘n’ roll in tempo and instrumentation. Also nearly good is “Round And Round,” a US number one in 1957, whose pleasing fugal structure would have been more bearable had the overbearing choir been given chloroform shortly before the session,, and rather more than good is “I Know,” a ballad requiring a deceptively wide vocal range and which emotionally comes out of “I Believe.” “I know what it means to be lost in the dark,” Como wishes to reassure us – the song is done as early Gene Pitney - and while there is precisely one tale of separation here (“For The Good Times”) and one song which hints at going bad (“Temptation”), it is sadly the case that Como is so instinctively good-natured and warm-hearted that it’s nearly impossible to picture him as a troubled soul. One simply does not – cannot – believe him, and so your appreciation of his “What Kind Of Fool Am I” will depend on your ability to picture Como as a lonely wastrel, his “Days Of Wine And Roses” as an alcoholic, his Love Story theme as Ryan O’Neal (and unlike Andy Williams, who got straight to the heart of both latter songs, Como doesn’t convince; despite a suspected Williams impression halfway through “Wine And Roses” [“The lonely night discloses…,” whose effect is rapidly negated by a dreadful, windy solo soprano who has clearly wandered in from a posthumous Jim Reeves session], and he drops the coda of “Where Do I Begin” entirely, failing to claim the key words “wild” and “soul” as his own; rather skating across them) – and, by these standards, the disturbed Como is a failure.

In terms of covers, too, the fifties Como remains unresolved. Frankie Laine stayed on top for eighteen weeks because he sings “I Believe” as though in the wildest corner of the darkest room; to himself, intensely and incandescently. Whereas the Cinemascope gloop of the overcooked arrangement, and more fatally Como’s double-tracked vocal, destroy any empathy. It is as though we are gathered at the end of one of his interminable seasonal TV specials, crucifix on the wall, family in fervent prayer. Worse is “Hello Young Lovers” from The King And I, now recast as an “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” ripoff (complete with the same trombone riff) and about the least qualified song to be recast as such. Elsewhere the creeping feeling (“Upon my knees to her I’m creeping,” sings Como on “Prisoner Of Love” – that must have been painful) of TPL nostalgia is magnified by the undistinguished presence of “You Make Me Feel So Young,” the first track on the first album I wrote about. In the intervening years I come across records like this and wonder whether I’ve made any progress at all (entries #2 and #3 are also represented, as detailed above).

As we move into the sixties and past “Delaware” – it is hardly surprising that, after the latter, Como did not return to the UK singles chart top ten for eleven years – one wonders how Como got through the decade. 1962’s “Caterina” is vile, holiday tourism at its crassest (“Purdy miss, purdy miss,” “AH HAH HAH,” “ecstasy” rhyming with “si si si”), and after that it was into the lounge for him. I’m not sure as to which decade his “Moonglow” belongs, but it sounds early sixties to me; the backing singers are for once sympathetic, and leading from their bass acappella introduction to a floating world of oboe, vibes and bass clarinet – Como’s “show-ow-wow” flutters like a Red Admiral towards the resolving “heavenly songs” – which would not be at all out of place on Pet Sounds, and both vocal and accompaniment demonstrate one road Como really should have taken a lot earlier. His “Dear Hearts & Gentle People,” doubtless intended as a heartfelt tribute to the stalwart burghers of Canonburg, Pennsylvania, from whence Como came, is detonated by a stupid Dixieland brass arrangement. “I Love You & Don’t You Forget It” is strictly lounge kitsch, though not unaware of its own absurdities (“That makes twenty times that I’ve said it!” – and there is a false ending). 1969’s bizarre “Seattle” sounds like a tourist board commission (and there is a certain overlap with “Different Drum” – which, I wonder, came first?) but actually comes from a long-forgotten Bobby Sherman TV series entitled Here Come The Brides. Perry Como goes flower power? Things were clearly in a fix.

The seventies are ushered in by a bravura “Without A Song,” recorded live in Las Vegas in June 1970; bravura enough, anyway, to make you forget that the song dates back to 1929, as Como twice gets his high C on the word – that word again – “soul.” Of “Close To You” and “Raindrops,” the best that can be said about Como’s return to Bacharach and David is that his versions sound like experiments in testing how close these songs are to “Magic Moments.” Sadly his “We’ve Only Just Begun” proves how right the Carpenters were to use themselves as their own backing singers; his versions sound flaccid and indulgent in comparison, while the count-up to eight in “Raindrops” makes me ask whether he had the Sesame Street audience in mind. He just does not get David Gates’ “If” (despite his voice break on the “slowly” of “spinning slowly down to die”). As for his Sound Gallery spy capers cover of “Temptation,” the less said, the better.

“It’s Impossible” brought him back to the top ten, both in the US and UK, and it remains a wonderful song, with that subtle piano (cascading with obvious onomatopoeia at Como’s “feel you running through me”) and the emotional equation now honed to something approaching perfection. The follow-up, Rod McKuen’s “I Think Of You,” was better still, its lyrical and emotional settings more ambiguous, and Como still demonstrating with his “I” (just as he did in the “and” on “When You Were Sweet 16”) his capability of making a word sounding like somebody unrolling a cigarette paper to reveal priceless gold. The 1973 hits remain exemplars of modern popular song – the absence of backing singers and the more open arrangements giving Como more space to inhabit the songs, as he should always have done. Yet his reading of the Everlys’ “Walk Right Back” raises the question of whether anything has been learned; those backing singers have returned, an “audible lace doily on the song” in Lena’s words.

Perhaps the final mystery of Perry Como is that there is no mystery, that here was someone satisfied to sing anything he was given, who lacked Sinatra’s ability to say no, whose brand of nonchalance was completely different from Dino’s (Martin gave the impression of caring so little that he might as well fade into invisibility; Como sang the songs but cared about his family and his own life more). His work is palpably greater when his voice is allowed to exist at, and as, the centre of the song. Weigh him down with too much baggage and he’ll sink like a stone. Make him too light and he’ll fly away. Be too proud and he’ll be singing for the barbershop forever (“Sweet 16” is a barbershop song par excellence).

Towards the end of side one, however, he reaches the ideal, and gets it; “Try To Remember,” from the long-running Broadway musical The Fantastics, and recorded sometime in the late sixties; a feathery ballad, and it’s easy to sing it and drown in its high-faluting wordplay. But Como’s performance is humble, searching, profound; the backing singers keep their distance, and with his “Follow”s and the patient acoustic guitar waltz, we realise that we could be listening to Scott Walker. Make no mistake; I’m not setting up 40 Greatest as a kind of good cop counterpart to another restless 1975 double album on RCA with a black cover and the artist in profile. Even if he had tried – and he would never have tried – Perry Como is not Metal Machine Music (although I find the latter oddly a lot more calming listen). But what, who, was he, this man who lived blamelessly until six days prior to his eighty-ninth birthday, when he literally fell asleep, and passed on? There are better, fuller compilations of his work now available on CD. But the life of the man as lived and documented, and the music heard here, do not quite add up. There is a discrepancy, inexplicable and possibly unexplainable, that makes the listener think: what is this man hiding from us? The answer? It was most likely nothing; a pleasant man singing an easy song, maybe a little morose about the probability that he’d be teeing off late if this session doesn’t get wrapped up. The ball of sun, the oval moon – both referred to in “Round And Round” – what exactly do these mean, again? “The silver moon will fall too soon” (“Wine And Roses”). Was he telling us something there? A difficult case, and probably an insoluble one. But don’t fall asleep on the job.

(#162: 22 November 1975, 5 weeks; 10 January 1976, 1 week)

Track listing: Magic Moments/Caterina/Catch A Falling Star/I Know/When You Were Sweet 16/I Believe/Try To Remember/Love Makes The World Go Round/Prisoner Of Love/Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes/Hot Diggity/Round And Round/If I Loved You/Hello Young Lovers/Delaware/Moonglow/Killing Me Softly/More/Dear Hearts & Gentle People/I Love You & Don’t You Forget It/And I Love You So/For The Good Times/Close To You/Seattle/Tie A Yellow Ribbon/Walk Right Back/What Kind Of Fool Am I/Days Of Wine And Roses/Where Do I Begin/Without A Song/It’s Impossible/I Think Of You/If/We’ve Only Just Begun/I Want To Give/Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head/You Make Me Feel So Young/Temptation/The Way We Were/Sing

(Author’s Note: I am well aware that several reputable chart sources list this album as being entitled 40 Greatest Hits, but both the front and back cover and the labels on all four sides of my LP copy say 40 Greatest and thus this is how I am billing it. The back cover does inform me that “THIS EXCITING L.P. IS ALSO NOW AVAILABLE ON CASSETTE AND 8-TRACK,” but since I have not found a copy in either of these formats – I fear that sending a cheque or postal order for £3.99 plus 25p for postage and handling might prove futile – this will have to do. I note that the spine of the album credits the title as FORTY GREATEST, but the sane and practical mind has to draw the line somewhere. Track titles, though mostly incomplete and/or deficient in punctuation, are listed as they appear on the back cover for similar sanity-preserving reasons)

“Pleasant, easy, and a tad morose”; that’s Julie Powell in her book Cleaving, describing something else completely, but it was the phrase Lena remembered and applied to the voice and delivery of Perry Como. On balance this double package looks much more fun and attractive than the Jim Reeves one – K-Tel having presumably won the RCA licensing rights over Arcade – with a haiku-like biographical sleevenote written with commendable concision, plenty of photos from different eras of Como, and endorsements from celebrities of the calibre of Irving Berlin, Johnny Mercer, Mel Tormé and Gordon Jenkins; all still alive in 1975, and all relating to the singer’s impeccable technical standards and the elusive spark known as “warmth.” Warm enough to send this compilation under the Christmas trees of innumerable mothers over that Christmas.

So I naturally thought that a couple of hours in Como’s company would prove a lot less cumbersome than two hours of Jim Reeves. Not so. If anything I found these forty songs – in reality thirty-four, once you discount the six tracks pulled from Como’s previously discussed And I Love You So album – rather tougher going, and it has to be said that the prospect of slumber was only narrowly averted as, towards the end of the recital, Como sleepwalked through yet another neutralised seventies movie theme (“The Way We Were,” although my mind began to wander into abstraction somewhere in the midst of “We’ve Only Just Begun”). Indeed many of these tracks belie the common assumption of Como being the natural, easy-going, microphone-caressing successor to Bing Crosby, enough to make me wonder whether RCA ever really knew what to do with him, or whether he was content enough to deal with whatever RCA threw at him.

The question one has to ask is: what does this album tell us about Perry Como, both about his music and about him as a human being? The answer is a rather confused picture, but it is important to try to address it since Como is one of the biggest mysteries this tale is likely to come across. It would not be worth the time or effort of writers such as Kitty Kelley or Nick Tosches to delve into Como’s life, since it reveals absolutely no subtext and tells absolutely no stories. Sinatra and Martin had their empowering demons, but Como was a barber who one day found that he could sing and set to doing something about it; and when he became famous he preferred to remain out of the spotlight and devote himself to his family. He was married to the same woman for some sixty-five years; there is no dirt to be uncovered, no Crosby kin horror stories of domestic violence, a totally clean sheet, so clean as to be a blank. He did what he did and when he wasn’t doing it he was a caring and devout husband, father and grandfather, and sometimes he would slope off to play golf. His was a very WASP Eisenhower dream; and while a cynic might posit that he subscribed to many dullard right-wing beliefs, there is no concrete evidence to suggest anything other than what I see when I try to picture Como the family patriarch in my mind – namely Howard Cunningham from Happy Days, laidback, tolerant of his family’s misdemeanours, philosophical, fatalistic and, above all, amiable (politically I suspect him to have been a Republican of the Eisenhower type; moderate, hard-working, loyal to family and country, not even thinking that there was another way).

So perhaps that was the secret of Como’s appeal; an Everyman (if the term “Everyman” implies “averageness”), a nice, decent, ordinary guy, straight as a die, who happened to be able to sing his ass off and not even let you know that it was any kind of an effort, who sat down on stage in his rocking chair and/or wearing a sensible jumper like he’d just looked in from the front room. The kind of guy who could sing dumb novelty songs and searing ballads about the sun, the moon and the stars and make it all fit.

But the picture presented by 40 Greatest doesn’t quite fit, and maybe that’s because it’s incomplete. Although the album encompasses everything from his first recording (“Prisoner Of Love," from 1945) to his last hit (“I Want To Give”), many hits are missed out, and undue prominence given to Como’s seventies output; aside from the aforementioned And I Love You So, 1971’s It’s Impossible and 1974’s Perry albums are also generously sampled. Hence important records like “Papa Loves Mambo,” “Surrender,” “Wanted,” “Glendora,” “Ko Ko Mo” and others do not appear at all. What remains is a confused and confusing portrait of someone perhaps a little too nice and compliant for his own good, someone content that the industry should know what constitutes a “hit” and happy to go along with their suggestions.

With “Prisoner Of Love,” RCA looked to be searching for an alternative Mario Lanza. The song was already fourteen years old – and yes, it’s the same “Prisoner Of Love” subsequently attacked by James Brown – and plays like an overblown Victorian melodrama. Against the over-stuffed orchestration, Como has no option but to bellow the song as though it were the last act of Tosca; when his voice rises for emotional emphasis, it has a tendency to become strident. His essay on Carousel’s “If I Loved You” is also problematic since, despite a terrific vocal performance, he cannot breathe within the corset of the glutinous arrangement, which seems to hold no room for people. In addition, there is a running problem with this album in the form of obstinately intrusive backing singers; the early “When You Were Sweet 16” is a case in point – Como delivers a near-perfect out-of-tempo reading of the song, and it should have ended there; but no, here comes the celeste, and then the ghastly choir, to ruin the experience.

Como’s output into and through the fifties (and even unto the early sixties) suffered from the same kind of emotional schizophrenia. Essentially there is a split between goofy bits of nonsense like “Hot Diggity” and the repulsive “Delaware” (which latter unfortunately reminds me, musically, of an unwanted cross between the Horst Wessel song and “Ballad Of The Green Berets”) and more standard fare, like the sentimental but hopelessly dated waltz “More”; 1953’s transatlantic number one “Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes” whose essential lightness is undermined by barking Three Amigos backing vocals and snarling trombones; and 1958’s lunge at the rock ‘n’ roll market, “Love Makes The World Go Round,” a far bigger hit in the UK than in the US. Como despised rock ‘n’ roll and makes little effort to disguise his contempt in his vocal here, even resorting to sending up the “yay yay and a yay-YEAH!” backing vocals. Contempt? Actually he sounds as though he is falling asleep.

A better rapprochement with nowness was achieved in the historic 1958 double-sided smash “Magic Moments” – early Bacharach and David with jaunty whistling and bassoon, where the backing singers work with, rather than against, Como for a change (although the song and record are still really corny; “clutch down” to rhyme with “touchdown”?) - and the lovely “Catch A Falling Star,” with its “Spanish Harlem”-anticipating guitar (it suddenly rises in response to Como’s “tap you on the shoulder”) and subtler acknowledgements to rock ‘n’ roll in tempo and instrumentation. Also nearly good is “Round And Round,” a US number one in 1957, whose pleasing fugal structure would have been more bearable had the overbearing choir been given chloroform shortly before the session,, and rather more than good is “I Know,” a ballad requiring a deceptively wide vocal range and which emotionally comes out of “I Believe.” “I know what it means to be lost in the dark,” Como wishes to reassure us – the song is done as early Gene Pitney - and while there is precisely one tale of separation here (“For The Good Times”) and one song which hints at going bad (“Temptation”), it is sadly the case that Como is so instinctively good-natured and warm-hearted that it’s nearly impossible to picture him as a troubled soul. One simply does not – cannot – believe him, and so your appreciation of his “What Kind Of Fool Am I” will depend on your ability to picture Como as a lonely wastrel, his “Days Of Wine And Roses” as an alcoholic, his Love Story theme as Ryan O’Neal (and unlike Andy Williams, who got straight to the heart of both latter songs, Como doesn’t convince; despite a suspected Williams impression halfway through “Wine And Roses” [“The lonely night discloses…,” whose effect is rapidly negated by a dreadful, windy solo soprano who has clearly wandered in from a posthumous Jim Reeves session], and he drops the coda of “Where Do I Begin” entirely, failing to claim the key words “wild” and “soul” as his own; rather skating across them) – and, by these standards, the disturbed Como is a failure.

In terms of covers, too, the fifties Como remains unresolved. Frankie Laine stayed on top for eighteen weeks because he sings “I Believe” as though in the wildest corner of the darkest room; to himself, intensely and incandescently. Whereas the Cinemascope gloop of the overcooked arrangement, and more fatally Como’s double-tracked vocal, destroy any empathy. It is as though we are gathered at the end of one of his interminable seasonal TV specials, crucifix on the wall, family in fervent prayer. Worse is “Hello Young Lovers” from The King And I, now recast as an “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” ripoff (complete with the same trombone riff) and about the least qualified song to be recast as such. Elsewhere the creeping feeling (“Upon my knees to her I’m creeping,” sings Como on “Prisoner Of Love” – that must have been painful) of TPL nostalgia is magnified by the undistinguished presence of “You Make Me Feel So Young,” the first track on the first album I wrote about. In the intervening years I come across records like this and wonder whether I’ve made any progress at all (entries #2 and #3 are also represented, as detailed above).

As we move into the sixties and past “Delaware” – it is hardly surprising that, after the latter, Como did not return to the UK singles chart top ten for eleven years – one wonders how Como got through the decade. 1962’s “Caterina” is vile, holiday tourism at its crassest (“Purdy miss, purdy miss,” “AH HAH HAH,” “ecstasy” rhyming with “si si si”), and after that it was into the lounge for him. I’m not sure as to which decade his “Moonglow” belongs, but it sounds early sixties to me; the backing singers are for once sympathetic, and leading from their bass acappella introduction to a floating world of oboe, vibes and bass clarinet – Como’s “show-ow-wow” flutters like a Red Admiral towards the resolving “heavenly songs” – which would not be at all out of place on Pet Sounds, and both vocal and accompaniment demonstrate one road Como really should have taken a lot earlier. His “Dear Hearts & Gentle People,” doubtless intended as a heartfelt tribute to the stalwart burghers of Canonburg, Pennsylvania, from whence Como came, is detonated by a stupid Dixieland brass arrangement. “I Love You & Don’t You Forget It” is strictly lounge kitsch, though not unaware of its own absurdities (“That makes twenty times that I’ve said it!” – and there is a false ending). 1969’s bizarre “Seattle” sounds like a tourist board commission (and there is a certain overlap with “Different Drum” – which, I wonder, came first?) but actually comes from a long-forgotten Bobby Sherman TV series entitled Here Come The Brides. Perry Como goes flower power? Things were clearly in a fix.

The seventies are ushered in by a bravura “Without A Song,” recorded live in Las Vegas in June 1970; bravura enough, anyway, to make you forget that the song dates back to 1929, as Como twice gets his high C on the word – that word again – “soul.” Of “Close To You” and “Raindrops,” the best that can be said about Como’s return to Bacharach and David is that his versions sound like experiments in testing how close these songs are to “Magic Moments.” Sadly his “We’ve Only Just Begun” proves how right the Carpenters were to use themselves as their own backing singers; his versions sound flaccid and indulgent in comparison, while the count-up to eight in “Raindrops” makes me ask whether he had the Sesame Street audience in mind. He just does not get David Gates’ “If” (despite his voice break on the “slowly” of “spinning slowly down to die”). As for his Sound Gallery spy capers cover of “Temptation,” the less said, the better.

“It’s Impossible” brought him back to the top ten, both in the US and UK, and it remains a wonderful song, with that subtle piano (cascading with obvious onomatopoeia at Como’s “feel you running through me”) and the emotional equation now honed to something approaching perfection. The follow-up, Rod McKuen’s “I Think Of You,” was better still, its lyrical and emotional settings more ambiguous, and Como still demonstrating with his “I” (just as he did in the “and” on “When You Were Sweet 16”) his capability of making a word sounding like somebody unrolling a cigarette paper to reveal priceless gold. The 1973 hits remain exemplars of modern popular song – the absence of backing singers and the more open arrangements giving Como more space to inhabit the songs, as he should always have done. Yet his reading of the Everlys’ “Walk Right Back” raises the question of whether anything has been learned; those backing singers have returned, an “audible lace doily on the song” in Lena’s words.

Perhaps the final mystery of Perry Como is that there is no mystery, that here was someone satisfied to sing anything he was given, who lacked Sinatra’s ability to say no, whose brand of nonchalance was completely different from Dino’s (Martin gave the impression of caring so little that he might as well fade into invisibility; Como sang the songs but cared about his family and his own life more). His work is palpably greater when his voice is allowed to exist at, and as, the centre of the song. Weigh him down with too much baggage and he’ll sink like a stone. Make him too light and he’ll fly away. Be too proud and he’ll be singing for the barbershop forever (“Sweet 16” is a barbershop song par excellence).

Towards the end of side one, however, he reaches the ideal, and gets it; “Try To Remember,” from the long-running Broadway musical The Fantastics, and recorded sometime in the late sixties; a feathery ballad, and it’s easy to sing it and drown in its high-faluting wordplay. But Como’s performance is humble, searching, profound; the backing singers keep their distance, and with his “Follow”s and the patient acoustic guitar waltz, we realise that we could be listening to Scott Walker. Make no mistake; I’m not setting up 40 Greatest as a kind of good cop counterpart to another restless 1975 double album on RCA with a black cover and the artist in profile. Even if he had tried – and he would never have tried – Perry Como is not Metal Machine Music (although I find the latter oddly a lot more calming listen). But what, who, was he, this man who lived blamelessly until six days prior to his eighty-ninth birthday, when he literally fell asleep, and passed on? There are better, fuller compilations of his work now available on CD. But the life of the man as lived and documented, and the music heard here, do not quite add up. There is a discrepancy, inexplicable and possibly unexplainable, that makes the listener think: what is this man hiding from us? The answer? It was most likely nothing; a pleasant man singing an easy song, maybe a little morose about the probability that he’d be teeing off late if this session doesn’t get wrapped up. The ball of sun, the oval moon – both referred to in “Round And Round” – what exactly do these mean, again? “The silver moon will fall too soon” (“Wine And Roses”). Was he telling us something there? A difficult case, and probably an insoluble one. But don’t fall asleep on the job.

Sunday 25 March 2012

Perry COMO: 40 Greatest

(#162: 22 November 1975, 5 weeks; 10 January 1976, 1 week)

Track listing: Magic Moments/Caterina/Catch A Falling Star/I Know/When You Were Sweet 16/I Believe/Try To Remember/Love Makes The World Go Round/Prisoner Of Love/Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes/Hot Diggity/Round And Round/If I Loved You/Hello Young Lovers/Delaware/Moonglow/Killing Me Softly/More/Dear Hearts & Gentle People/I Love You & Don’t You Forget It/And I Love You So/For The Good Times/Close To You/Seattle/Tie A Yellow Ribbon/Walk Right Back/What Kind Of Fool Am I/Days Of Wine And Roses/Where Do I Begin/Without A Song/It’s Impossible/I Think Of You/If/We’ve Only Just Begun/I Want To Give/Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head/You Make Me Feel So Young/Temptation/The Way We Were/Sing

(Author’s Note: I am well aware that several reputable chart sources list this album as being entitled 40 Greatest Hits, but both the front and back cover and the labels on all four sides of my LP copy say 40 Greatest and thus this is how I am billing it. The back cover does inform me that “THIS EXCITING L.P. IS ALSO NOW AVAILABLE ON CASSETTE AND 8-TRACK,” but since I have not found a copy in either of these formats – I fear that sending a cheque or postal order for £3.99 plus 25p for postage and handling might prove futile – this will have to do. I note that the spine of the album credits the title as FORTY GREATEST, but the sane and practical mind has to draw the line somewhere. Track titles, though mostly incomplete and/or deficient in punctuation, are listed as they appear on the back cover for similar sanity-preserving reasons)

“Pleasant, easy, and a tad morose”; that’s Julie Powell in her book Cleaving, describing something else completely, but it was the phrase Lena remembered and applied to the voice and delivery of Perry Como. On balance this double package looks much more fun and attractive than the Jim Reeves one – K-Tel having presumably won the RCA licensing rights over Arcade – with a haiku-like biographical sleevenote written with commendable concision, plenty of photos from different eras of Como, and endorsements from celebrities of the calibre of Irving Berlin, Johnny Mercer, Mel Tormé and Gordon Jenkins; all still alive in 1975, and all relating to the singer’s impeccable technical standards and the elusive spark known as “warmth.” Warm enough to send this compilation under the Christmas trees of innumerable mothers over that Christmas.

So I naturally thought that a couple of hours in Como’s company would prove a lot less cumbersome than two hours of Jim Reeves. Not so. If anything I found these forty songs – in reality thirty-four, once you discount the six tracks pulled from Como’s previously discussed And I Love You So album – rather tougher going, and it has to be said that the prospect of slumber was only narrowly averted as, towards the end of the recital, Como sleepwalked through yet another neutralised seventies movie theme (“The Way We Were,” although my mind began to wander into abstraction somewhere in the midst of “We’ve Only Just Begun”). Indeed many of these tracks belie the common assumption of Como being the natural, easy-going, microphone-caressing successor to Bing Crosby, enough to make me wonder whether RCA ever really knew what to do with him, or whether he was content enough to deal with whatever RCA threw at him.

The question one has to ask is: what does this album tell us about Perry Como, both about his music and about him as a human being? The answer is a rather confused picture, but it is important to try to address it since Como is one of the biggest mysteries this tale is likely to come across. It would not be worth the time or effort of writers such as Kitty Kelley or Nick Tosches to delve into Como’s life, since it reveals absolutely no subtext and tells absolutely no stories. Sinatra and Martin had their empowering demons, but Como was a barber who one day found that he could sing and set to doing something about it; and when he became famous he preferred to remain out of the spotlight and devote himself to his family. He was married to the same woman for some sixty-five years; there is no dirt to be uncovered, no Crosby kin horror stories of domestic violence, a totally clean sheet, so clean as to be a blank. He did what he did and when he wasn’t doing it he was a caring and devout husband, father and grandfather, and sometimes he would slope off to play golf. His was a very WASP Eisenhower dream; and while a cynic might posit that he subscribed to many dullard right-wing beliefs, there is no concrete evidence to suggest anything other than what I see when I try to picture Como the family patriarch in my mind – namely Howard Cunningham from Happy Days, laidback, tolerant of his family’s misdemeanours, philosophical, fatalistic and, above all, amiable (politically I suspect him to have been a Republican of the Eisenhower type; moderate, hard-working, loyal to family and country, not even thinking that there was another way).

So perhaps that was the secret of Como’s appeal; an Everyman (if the term “Everyman” implies “averageness”), a nice, decent, ordinary guy, straight as a die, who happened to be able to sing his ass off and not even let you know that it was any kind of an effort, who sat down on stage in his rocking chair and/or wearing a sensible jumper like he’d just looked in from the front room. The kind of guy who could sing dumb novelty songs and searing ballads about the sun, the moon and the stars and make it all fit.

But the picture presented by 40 Greatest doesn’t quite fit, and maybe that’s because it’s incomplete. Although the album encompasses everything from his first recording (“Prisoner Of Love," from 1945) to his last hit (“I Want To Give”), many hits are missed out, and undue prominence given to Como’s seventies output; aside from the aforementioned And I Love You So, 1971’s It’s Impossible and 1974’s Perry albums are also generously sampled. Hence important records like “Papa Loves Mambo,” “Surrender,” “Wanted,” “Glendora,” “Ko Ko Mo” and others do not appear at all. What remains is a confused and confusing portrait of someone perhaps a little too nice and compliant for his own good, someone content that the industry should know what constitutes a “hit” and happy to go along with their suggestions.

With “Prisoner Of Love,” RCA looked to be searching for an alternative Mario Lanza. The song was already fourteen years old – and yes, it’s the same “Prisoner Of Love” subsequently attacked by James Brown – and plays like an overblown Victorian melodrama. Against the over-stuffed orchestration, Como has no option but to bellow the song as though it were the last act of Tosca; when his voice rises for emotional emphasis, it has a tendency to become strident. His essay on Carousel’s “If I Loved You” is also problematic since, despite a terrific vocal performance, he cannot breathe within the corset of the glutinous arrangement, which seems to hold no room for people. In addition, there is a running problem with this album in the form of obstinately intrusive backing singers; the early “When You Were Sweet 16” is a case in point – Como delivers a near-perfect out-of-tempo reading of the song, and it should have ended there; but no, here comes the celeste, and then the ghastly choir, to ruin the experience.

Como’s output into and through the fifties (and even unto the early sixties) suffered from the same kind of emotional schizophrenia. Essentially there is a split between goofy bits of nonsense like “Hot Diggity” and the repulsive “Delaware” (which latter unfortunately reminds me, musically, of an unwanted cross between the Horst Wessel song and “Ballad Of The Green Berets”) and more standard fare, like the sentimental but hopelessly dated waltz “More”; 1953’s transatlantic number one “Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes” whose essential lightness is undermined by barking Three Amigos backing vocals and snarling trombones; and 1958’s lunge at the rock ‘n’ roll market, “Love Makes The World Go Round,” a far bigger hit in the UK than in the US. Como despised rock ‘n’ roll and makes little effort to disguise his contempt in his vocal here, even resorting to sending up the “yay yay and a yay-YEAH!” backing vocals. Contempt? Actually he sounds as though he is falling asleep.

A better rapprochement with nowness was achieved in the historic 1958 double-sided smash “Magic Moments” – early Bacharach and David with jaunty whistling and bassoon, where the backing singers work with, rather than against, Como for a change (although the song and record are still really corny; “clutch down” to rhyme with “touchdown”?) - and the lovely “Catch A Falling Star,” with its “Spanish Harlem”-anticipating guitar (it suddenly rises in response to Como’s “tap you on the shoulder”) and subtler acknowledgements to rock ‘n’ roll in tempo and instrumentation. Also nearly good is “Round And Round,” a US number one in 1957, whose pleasing fugal structure would have been more bearable had the overbearing choir been given chloroform shortly before the session,, and rather more than good is “I Know,” a ballad requiring a deceptively wide vocal range and which emotionally comes out of “I Believe.” “I know what it means to be lost in the dark,” Como wishes to reassure us – the song is done as early Gene Pitney - and while there is precisely one tale of separation here (“For The Good Times”) and one song which hints at going bad (“Temptation”), it is sadly the case that Como is so instinctively good-natured and warm-hearted that it’s nearly impossible to picture him as a troubled soul. One simply does not – cannot – believe him, and so your appreciation of his “What Kind Of Fool Am I” will depend on your ability to picture Como as a lonely wastrel, his “Days Of Wine And Roses” as an alcoholic, his Love Story theme as Ryan O’Neal (and unlike Andy Williams, who got straight to the heart of both latter songs, Como doesn’t convince; despite a suspected Williams impression halfway through “Wine And Roses” [“The lonely night discloses…,” whose effect is rapidly negated by a dreadful, windy solo soprano who has clearly wandered in from a posthumous Jim Reeves session], and he drops the coda of “Where Do I Begin” entirely, failing to claim the key words “wild” and “soul” as his own; rather skating across them) – and, by these standards, the disturbed Como is a failure.

In terms of covers, too, the fifties Como remains unresolved. Frankie Laine stayed on top for eighteen weeks because he sings “I Believe” as though in the wildest corner of the darkest room; to himself, intensely and incandescently. Whereas the Cinemascope gloop of the overcooked arrangement, and more fatally Como’s double-tracked vocal, destroy any empathy. It is as though we are gathered at the end of one of his interminable seasonal TV specials, crucifix on the wall, family in fervent prayer. Worse is “Hello Young Lovers” from The King And I, now recast as an “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” ripoff (complete with the same trombone riff) and about the least qualified song to be recast as such. Elsewhere the creeping feeling (“Upon my knees to her I’m creeping,” sings Como on “Prisoner Of Love” – that must have been painful) of TPL nostalgia is magnified by the undistinguished presence of “You Make Me Feel So Young,” the first track on the first album I wrote about. In the intervening years I come across records like this and wonder whether I’ve made any progress at all (entries #2 and #3 are also represented, as detailed above).

As we move into the sixties and past “Delaware” – it is hardly surprising that, after the latter, Como did not return to the UK singles chart top ten for eleven years – one wonders how Como got through the decade. 1962’s “Caterina” is vile, holiday tourism at its crassest (“Purdy miss, purdy miss,” “AH HAH HAH,” “ecstasy” rhyming with “si si si”), and after that it was into the lounge for him. I’m not sure as to which decade his “Moonglow” belongs, but it sounds early sixties to me; the backing singers are for once sympathetic, and leading from their bass acappella introduction to a floating world of oboe, vibes and bass clarinet – Como’s “show-ow-wow” flutters like a Red Admiral towards the resolving “heavenly songs” – which would not be at all out of place on Pet Sounds, and both vocal and accompaniment demonstrate one road Como really should have taken a lot earlier. His “Dear Hearts & Gentle People,” doubtless intended as a heartfelt tribute to the stalwart burghers of Canonburg, Pennsylvania, from whence Como came, is detonated by a stupid Dixieland brass arrangement. “I Love You & Don’t You Forget It” is strictly lounge kitsch, though not unaware of its own absurdities (“That makes twenty times that I’ve said it!” – and there is a false ending). 1969’s bizarre “Seattle” sounds like a tourist board commission (and there is a certain overlap with “Different Drum” – which, I wonder, came first?) but actually comes from a long-forgotten Bobby Sherman TV series entitled Here Come The Brides. Perry Como goes flower power? Things were clearly in a fix.

The seventies are ushered in by a bravura “Without A Song,” recorded live in Las Vegas in June 1970; bravura enough, anyway, to make you forget that the song dates back to 1929, as Como twice gets his high C on the word – that word again – “soul.” Of “Close To You” and “Raindrops,” the best that can be said about Como’s return to Bacharach and David is that his versions sound like experiments in testing how close these songs are to “Magic Moments.” Sadly his “We’ve Only Just Begun” proves how right the Carpenters were to use themselves as their own backing singers; his versions sound flaccid and indulgent in comparison, while the count-up to eight in “Raindrops” makes me ask whether he had the Sesame Street audience in mind. He just does not get David Gates’ “If” (despite his voice break on the “slowly” of “spinning slowly down to die”). As for his Sound Gallery spy capers cover of “Temptation,” the less said, the better.

“It’s Impossible” brought him back to the top ten, both in the US and UK, and it remains a wonderful song, with that subtle piano (cascading with obvious onomatopoeia at Como’s “feel you running through me”) and the emotional equation now honed to something approaching perfection. The follow-up, Rod McKuen’s “I Think Of You,” was better still, its lyrical and emotional settings more ambiguous, and Como still demonstrating with his “I” (just as he did in the “and” on “When You Were Sweet 16”) his capability of making a word sounding like somebody unrolling a cigarette paper to reveal priceless gold. The 1973 hits remain exemplars of modern popular song – the absence of backing singers and the more open arrangements giving Como more space to inhabit the songs, as he should always have done. Yet his reading of the Everlys’ “Walk Right Back” raises the question of whether anything has been learned; those backing singers have returned, an “audible lace doily on the song” in Lena’s words.

Perhaps the final mystery of Perry Como is that there is no mystery, that here was someone satisfied to sing anything he was given, who lacked Sinatra’s ability to say no, whose brand of nonchalance was completely different from Dino’s (Martin gave the impression of caring so little that he might as well fade into invisibility; Como sang the songs but cared about his family and his own life more). His work is palpably greater when his voice is allowed to exist at, and as, the centre of the song. Weigh him down with too much baggage and he’ll sink like a stone. Make him too light and he’ll fly away. Be too proud and he’ll be singing for the barbershop forever (“Sweet 16” is a barbershop song par excellence).

Towards the end of side one, however, he reaches the ideal, and gets it; “Try To Remember,” from the long-running Broadway musical The Fantastics, and recorded sometime in the late sixties; a feathery ballad, and it’s easy to sing it and drown in its high-faluting wordplay. But Como’s performance is humble, searching, profound; the backing singers keep their distance, and with his “Follow”s and the patient acoustic guitar waltz, we realise that we could be listening to Scott Walker. Make no mistake; I’m not setting up 40 Greatest as a kind of good cop counterpart to another restless 1975 double album on RCA with a black cover and the artist in profile. Even if he had tried – and he would never have tried – Perry Como is not Metal Machine Music (although I find the latter oddly a lot more calming listen). But what, who, was he, this man who lived blamelessly until six days prior to his eighty-ninth birthday, when he literally fell asleep, and passed on? There are better, fuller compilations of his work now available on CD. But the life of the man as lived and documented, and the music heard here, do not quite add up. There is a discrepancy, inexplicable and possibly unexplainable, that makes the listener think: what is this man hiding from us? The answer? It was most likely nothing; a pleasant man singing an easy song, maybe a little morose about the probability that he’d be teeing off late if this session doesn’t get wrapped up. The ball of sun, the oval moon – both referred to in “Round And Round” – what exactly do these mean, again? “The silver moon will fall too soon” (“Wine And Roses”). Was he telling us something there? A difficult case, and probably an insoluble one. But don’t fall asleep on the job.

(#162: 22 November 1975, 5 weeks; 10 January 1976, 1 week)

Track listing: Magic Moments/Caterina/Catch A Falling Star/I Know/When You Were Sweet 16/I Believe/Try To Remember/Love Makes The World Go Round/Prisoner Of Love/Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes/Hot Diggity/Round And Round/If I Loved You/Hello Young Lovers/Delaware/Moonglow/Killing Me Softly/More/Dear Hearts & Gentle People/I Love You & Don’t You Forget It/And I Love You So/For The Good Times/Close To You/Seattle/Tie A Yellow Ribbon/Walk Right Back/What Kind Of Fool Am I/Days Of Wine And Roses/Where Do I Begin/Without A Song/It’s Impossible/I Think Of You/If/We’ve Only Just Begun/I Want To Give/Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head/You Make Me Feel So Young/Temptation/The Way We Were/Sing

(Author’s Note: I am well aware that several reputable chart sources list this album as being entitled 40 Greatest Hits, but both the front and back cover and the labels on all four sides of my LP copy say 40 Greatest and thus this is how I am billing it. The back cover does inform me that “THIS EXCITING L.P. IS ALSO NOW AVAILABLE ON CASSETTE AND 8-TRACK,” but since I have not found a copy in either of these formats – I fear that sending a cheque or postal order for £3.99 plus 25p for postage and handling might prove futile – this will have to do. I note that the spine of the album credits the title as FORTY GREATEST, but the sane and practical mind has to draw the line somewhere. Track titles, though mostly incomplete and/or deficient in punctuation, are listed as they appear on the back cover for similar sanity-preserving reasons)

“Pleasant, easy, and a tad morose”; that’s Julie Powell in her book Cleaving, describing something else completely, but it was the phrase Lena remembered and applied to the voice and delivery of Perry Como. On balance this double package looks much more fun and attractive than the Jim Reeves one – K-Tel having presumably won the RCA licensing rights over Arcade – with a haiku-like biographical sleevenote written with commendable concision, plenty of photos from different eras of Como, and endorsements from celebrities of the calibre of Irving Berlin, Johnny Mercer, Mel Tormé and Gordon Jenkins; all still alive in 1975, and all relating to the singer’s impeccable technical standards and the elusive spark known as “warmth.” Warm enough to send this compilation under the Christmas trees of innumerable mothers over that Christmas.

So I naturally thought that a couple of hours in Como’s company would prove a lot less cumbersome than two hours of Jim Reeves. Not so. If anything I found these forty songs – in reality thirty-four, once you discount the six tracks pulled from Como’s previously discussed And I Love You So album – rather tougher going, and it has to be said that the prospect of slumber was only narrowly averted as, towards the end of the recital, Como sleepwalked through yet another neutralised seventies movie theme (“The Way We Were,” although my mind began to wander into abstraction somewhere in the midst of “We’ve Only Just Begun”). Indeed many of these tracks belie the common assumption of Como being the natural, easy-going, microphone-caressing successor to Bing Crosby, enough to make me wonder whether RCA ever really knew what to do with him, or whether he was content enough to deal with whatever RCA threw at him.

The question one has to ask is: what does this album tell us about Perry Como, both about his music and about him as a human being? The answer is a rather confused picture, but it is important to try to address it since Como is one of the biggest mysteries this tale is likely to come across. It would not be worth the time or effort of writers such as Kitty Kelley or Nick Tosches to delve into Como’s life, since it reveals absolutely no subtext and tells absolutely no stories. Sinatra and Martin had their empowering demons, but Como was a barber who one day found that he could sing and set to doing something about it; and when he became famous he preferred to remain out of the spotlight and devote himself to his family. He was married to the same woman for some sixty-five years; there is no dirt to be uncovered, no Crosby kin horror stories of domestic violence, a totally clean sheet, so clean as to be a blank. He did what he did and when he wasn’t doing it he was a caring and devout husband, father and grandfather, and sometimes he would slope off to play golf. His was a very WASP Eisenhower dream; and while a cynic might posit that he subscribed to many dullard right-wing beliefs, there is no concrete evidence to suggest anything other than what I see when I try to picture Como the family patriarch in my mind – namely Howard Cunningham from Happy Days, laidback, tolerant of his family’s misdemeanours, philosophical, fatalistic and, above all, amiable (politically I suspect him to have been a Republican of the Eisenhower type; moderate, hard-working, loyal to family and country, not even thinking that there was another way).

So perhaps that was the secret of Como’s appeal; an Everyman (if the term “Everyman” implies “averageness”), a nice, decent, ordinary guy, straight as a die, who happened to be able to sing his ass off and not even let you know that it was any kind of an effort, who sat down on stage in his rocking chair and/or wearing a sensible jumper like he’d just looked in from the front room. The kind of guy who could sing dumb novelty songs and searing ballads about the sun, the moon and the stars and make it all fit.

But the picture presented by 40 Greatest doesn’t quite fit, and maybe that’s because it’s incomplete. Although the album encompasses everything from his first recording (“Prisoner Of Love," from 1945) to his last hit (“I Want To Give”), many hits are missed out, and undue prominence given to Como’s seventies output; aside from the aforementioned And I Love You So, 1971’s It’s Impossible and 1974’s Perry albums are also generously sampled. Hence important records like “Papa Loves Mambo,” “Surrender,” “Wanted,” “Glendora,” “Ko Ko Mo” and others do not appear at all. What remains is a confused and confusing portrait of someone perhaps a little too nice and compliant for his own good, someone content that the industry should know what constitutes a “hit” and happy to go along with their suggestions.

With “Prisoner Of Love,” RCA looked to be searching for an alternative Mario Lanza. The song was already fourteen years old – and yes, it’s the same “Prisoner Of Love” subsequently attacked by James Brown – and plays like an overblown Victorian melodrama. Against the over-stuffed orchestration, Como has no option but to bellow the song as though it were the last act of Tosca; when his voice rises for emotional emphasis, it has a tendency to become strident. His essay on Carousel’s “If I Loved You” is also problematic since, despite a terrific vocal performance, he cannot breathe within the corset of the glutinous arrangement, which seems to hold no room for people. In addition, there is a running problem with this album in the form of obstinately intrusive backing singers; the early “When You Were Sweet 16” is a case in point – Como delivers a near-perfect out-of-tempo reading of the song, and it should have ended there; but no, here comes the celeste, and then the ghastly choir, to ruin the experience.

Como’s output into and through the fifties (and even unto the early sixties) suffered from the same kind of emotional schizophrenia. Essentially there is a split between goofy bits of nonsense like “Hot Diggity” and the repulsive “Delaware” (which latter unfortunately reminds me, musically, of an unwanted cross between the Horst Wessel song and “Ballad Of The Green Berets”) and more standard fare, like the sentimental but hopelessly dated waltz “More”; 1953’s transatlantic number one “Don’t Let The Stars Get In Your Eyes” whose essential lightness is undermined by barking Three Amigos backing vocals and snarling trombones; and 1958’s lunge at the rock ‘n’ roll market, “Love Makes The World Go Round,” a far bigger hit in the UK than in the US. Como despised rock ‘n’ roll and makes little effort to disguise his contempt in his vocal here, even resorting to sending up the “yay yay and a yay-YEAH!” backing vocals. Contempt? Actually he sounds as though he is falling asleep.

A better rapprochement with nowness was achieved in the historic 1958 double-sided smash “Magic Moments” – early Bacharach and David with jaunty whistling and bassoon, where the backing singers work with, rather than against, Como for a change (although the song and record are still really corny; “clutch down” to rhyme with “touchdown”?) - and the lovely “Catch A Falling Star,” with its “Spanish Harlem”-anticipating guitar (it suddenly rises in response to Como’s “tap you on the shoulder”) and subtler acknowledgements to rock ‘n’ roll in tempo and instrumentation. Also nearly good is “Round And Round,” a US number one in 1957, whose pleasing fugal structure would have been more bearable had the overbearing choir been given chloroform shortly before the session,, and rather more than good is “I Know,” a ballad requiring a deceptively wide vocal range and which emotionally comes out of “I Believe.” “I know what it means to be lost in the dark,” Como wishes to reassure us – the song is done as early Gene Pitney - and while there is precisely one tale of separation here (“For The Good Times”) and one song which hints at going bad (“Temptation”), it is sadly the case that Como is so instinctively good-natured and warm-hearted that it’s nearly impossible to picture him as a troubled soul. One simply does not – cannot – believe him, and so your appreciation of his “What Kind Of Fool Am I” will depend on your ability to picture Como as a lonely wastrel, his “Days Of Wine And Roses” as an alcoholic, his Love Story theme as Ryan O’Neal (and unlike Andy Williams, who got straight to the heart of both latter songs, Como doesn’t convince; despite a suspected Williams impression halfway through “Wine And Roses” [“The lonely night discloses…,” whose effect is rapidly negated by a dreadful, windy solo soprano who has clearly wandered in from a posthumous Jim Reeves session], and he drops the coda of “Where Do I Begin” entirely, failing to claim the key words “wild” and “soul” as his own; rather skating across them) – and, by these standards, the disturbed Como is a failure.

In terms of covers, too, the fifties Como remains unresolved. Frankie Laine stayed on top for eighteen weeks because he sings “I Believe” as though in the wildest corner of the darkest room; to himself, intensely and incandescently. Whereas the Cinemascope gloop of the overcooked arrangement, and more fatally Como’s double-tracked vocal, destroy any empathy. It is as though we are gathered at the end of one of his interminable seasonal TV specials, crucifix on the wall, family in fervent prayer. Worse is “Hello Young Lovers” from The King And I, now recast as an “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” ripoff (complete with the same trombone riff) and about the least qualified song to be recast as such. Elsewhere the creeping feeling (“Upon my knees to her I’m creeping,” sings Como on “Prisoner Of Love” – that must have been painful) of TPL nostalgia is magnified by the undistinguished presence of “You Make Me Feel So Young,” the first track on the first album I wrote about. In the intervening years I come across records like this and wonder whether I’ve made any progress at all (entries #2 and #3 are also represented, as detailed above).

As we move into the sixties and past “Delaware” – it is hardly surprising that, after the latter, Como did not return to the UK singles chart top ten for eleven years – one wonders how Como got through the decade. 1962’s “Caterina” is vile, holiday tourism at its crassest (“Purdy miss, purdy miss,” “AH HAH HAH,” “ecstasy” rhyming with “si si si”), and after that it was into the lounge for him. I’m not sure as to which decade his “Moonglow” belongs, but it sounds early sixties to me; the backing singers are for once sympathetic, and leading from their bass acappella introduction to a floating world of oboe, vibes and bass clarinet – Como’s “show-ow-wow” flutters like a Red Admiral towards the resolving “heavenly songs” – which would not be at all out of place on Pet Sounds, and both vocal and accompaniment demonstrate one road Como really should have taken a lot earlier. His “Dear Hearts & Gentle People,” doubtless intended as a heartfelt tribute to the stalwart burghers of Canonburg, Pennsylvania, from whence Como came, is detonated by a stupid Dixieland brass arrangement. “I Love You & Don’t You Forget It” is strictly lounge kitsch, though not unaware of its own absurdities (“That makes twenty times that I’ve said it!” – and there is a false ending). 1969’s bizarre “Seattle” sounds like a tourist board commission (and there is a certain overlap with “Different Drum” – which, I wonder, came first?) but actually comes from a long-forgotten Bobby Sherman TV series entitled Here Come The Brides. Perry Como goes flower power? Things were clearly in a fix.

The seventies are ushered in by a bravura “Without A Song,” recorded live in Las Vegas in June 1970; bravura enough, anyway, to make you forget that the song dates back to 1929, as Como twice gets his high C on the word – that word again – “soul.” Of “Close To You” and “Raindrops,” the best that can be said about Como’s return to Bacharach and David is that his versions sound like experiments in testing how close these songs are to “Magic Moments.” Sadly his “We’ve Only Just Begun” proves how right the Carpenters were to use themselves as their own backing singers; his versions sound flaccid and indulgent in comparison, while the count-up to eight in “Raindrops” makes me ask whether he had the Sesame Street audience in mind. He just does not get David Gates’ “If” (despite his voice break on the “slowly” of “spinning slowly down to die”). As for his Sound Gallery spy capers cover of “Temptation,” the less said, the better.

“It’s Impossible” brought him back to the top ten, both in the US and UK, and it remains a wonderful song, with that subtle piano (cascading with obvious onomatopoeia at Como’s “feel you running through me”) and the emotional equation now honed to something approaching perfection. The follow-up, Rod McKuen’s “I Think Of You,” was better still, its lyrical and emotional settings more ambiguous, and Como still demonstrating with his “I” (just as he did in the “and” on “When You Were Sweet 16”) his capability of making a word sounding like somebody unrolling a cigarette paper to reveal priceless gold. The 1973 hits remain exemplars of modern popular song – the absence of backing singers and the more open arrangements giving Como more space to inhabit the songs, as he should always have done. Yet his reading of the Everlys’ “Walk Right Back” raises the question of whether anything has been learned; those backing singers have returned, an “audible lace doily on the song” in Lena’s words.

Perhaps the final mystery of Perry Como is that there is no mystery, that here was someone satisfied to sing anything he was given, who lacked Sinatra’s ability to say no, whose brand of nonchalance was completely different from Dino’s (Martin gave the impression of caring so little that he might as well fade into invisibility; Como sang the songs but cared about his family and his own life more). His work is palpably greater when his voice is allowed to exist at, and as, the centre of the song. Weigh him down with too much baggage and he’ll sink like a stone. Make him too light and he’ll fly away. Be too proud and he’ll be singing for the barbershop forever (“Sweet 16” is a barbershop song par excellence).

Towards the end of side one, however, he reaches the ideal, and gets it; “Try To Remember,” from the long-running Broadway musical The Fantastics, and recorded sometime in the late sixties; a feathery ballad, and it’s easy to sing it and drown in its high-faluting wordplay. But Como’s performance is humble, searching, profound; the backing singers keep their distance, and with his “Follow”s and the patient acoustic guitar waltz, we realise that we could be listening to Scott Walker. Make no mistake; I’m not setting up 40 Greatest as a kind of good cop counterpart to another restless 1975 double album on RCA with a black cover and the artist in profile. Even if he had tried – and he would never have tried – Perry Como is not Metal Machine Music (although I find the latter oddly a lot more calming listen). But what, who, was he, this man who lived blamelessly until six days prior to his eighty-ninth birthday, when he literally fell asleep, and passed on? There are better, fuller compilations of his work now available on CD. But the life of the man as lived and documented, and the music heard here, do not quite add up. There is a discrepancy, inexplicable and possibly unexplainable, that makes the listener think: what is this man hiding from us? The answer? It was most likely nothing; a pleasant man singing an easy song, maybe a little morose about the probability that he’d be teeing off late if this session doesn’t get wrapped up. The ball of sun, the oval moon – both referred to in “Round And Round” – what exactly do these mean, again? “The silver moon will fall too soon” (“Wine And Roses”). Was he telling us something there? A difficult case, and probably an insoluble one. But don’t fall asleep on the job.

Sunday 18 March 2012

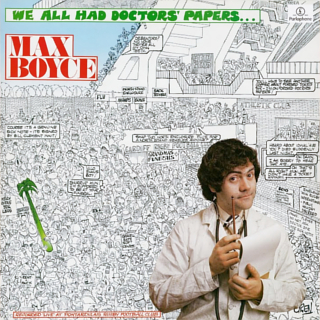

Max BOYCE: We All Had Doctors' Papers

(#161: 15 November 1975, 1 week)

Track listing: Sospan Fach/I Am An Entertainer/I Wandered Lonely/I Gave My Love A Debenture/Rhondda Grey/Slow, Men At Work/Deck Of Cards/Swansea Town/The Devil’s Marking Me/A’r Lan Y Mör/The Pontypool Front Row/Sospan Fach

“When I see the eight I think of the great Mervyn Davies, the greatest ‘number eight’ in the world.”

(Max Boyce, “Deck Of Cards”)

The man always had a good sense of timing. Not only did “Merv the Swerve” check out the day before his number came up on Then Play Long, but he also died exactly thirty-six years after captaining the Welsh team who beat France comfortably at Cardiff towards their historic Grand Slam victory – and the day before it would happen again, 16-9 at the Millennium Stadium, by a side generally thought to be at least the equivalent of the great seventies teams. Only a few days after his victory, while playing for Swansea in the Welsh Cup final against Pontypool, again at Cardiff, he collapsed on the pitch with a brain haemorrhage. He was lucky to have come through that – he later admitted that had he collapsed on an “obscure golf course,” that would have been it – but as a result he never played again, although he did flourish in subsequent spells as rugby coach and journalist. Nobody who remembers his cunning and tough tackles, his brilliant passing – the term “defender” scarcely did him justice – could deny that he was one of the greatest players the game of rugby union had seen.

I stress the term “rugby union” because all of the rugby-related humour and music within We All Had Doctors’ Papers is to do with this variant of the game. The term “rugby league” is mentioned only two or three times, and on one of these occasions the words are bleeped out as though they were expletives. Those who don’t recognise the differences between the two sports are probably unaware of the turbulent history which produced them, a story of paid versus unpaid, cushioned southerners against needful northerners, between dilettantism and need. Rugby league is supposed to produce a more visually exciting and stimulating game than rugby union, and also requires two fewer players (thirteen rather than fifteen). This is, however, probably the first instance of sport selling itself out in order to appease fickle, floating audiences; the point of rugby union is that, under its cover of aggression, it is as artful and tricky a pursuit as cricket. It is about long-term results rather than flashes in a glamorous pan.

But then We All Had Doctors’ Papers isn’t really about rugby, even though four of its songs, and much of the patter, are devoted to the subject, and it was recorded live (to a point; the recordings were made from several different performances, as the fadeouts and splicings betray) at the Pontardulais Rugby Club. It’s true that a full appreciation of the record involves an intimate understanding of the geography of South Wales and the comings and goings of their mid-seventies rugby clubs. More importantly, though, it’s about life, and the necessity to hold on to and maintain it.

It’s not really a “comedy” album either, and certainly isn’t the only “comedy” album that will be considered here, although it is frequently very funny indeed. I thought initially to prepare for this record by undertaking a full-length survey of comedic trends in 1975, but after a thousand or so words realised that this would be sorely inadequate, and most likely irrelevant. Better to say that Max Boyce is this tale’s most visible example of one of the most prominent trends in British comedy of the period, namely the tendency of long-serving folk musicians to move towards telling jokes.

There was also Mike Harding from Rochdale and Jasper Carrott from Birmingham, but the man who got the whole craze going was unquestionably Billy Connolly, who the following week would attain a UK number one single with his literal shaggy dog story reading of Tammy Wynette’s “D.I.V.O.R.C.E.” Although 1974’s double Solo Concert, taped at a pub in Airdrie, was not Connolly’s first “comedy” album, it proved his breakthrough; it sold in such astronomical qualities in Scotland that I don’t think I’ve come across a household which didn’t have a copy. Formerly one half of the Humblebums, with Gerry Rafferty, Connolly gradually realised that his between-songs patter was getting a better reaction than his songs, and realigned his act accordingly. Hence Solo Concert is mostly Connolly, ranting, musing and amusing, with occasional proficient banjo/guitar outings; major setpieces like “The Jobbie Weecha!” and “The Crucifixion,” reconstructions of tired pop songs (“Nobody’s Child,” “Ten Guitars,” “Long Haired Lover From Liverpool” – all get a good kicking here) and long ponderous strands where nothing much happens at all; an overlong and unfunny reminiscence of fifties camping barely raises a titter. But there was nothing else like it happening in Britain, and so the Big Yin prospered.

Connolly bothers me, especially after listening to the man (mistakenly) labelled his Welsh equivalent. There’s a continued undercurrent of aggression and contempt in Connolly’s work; you’re never quite sure whether he’s going to step down into the audience and bash someone over the head with his banjo. There’s a hard threat about his posture, an air of menace. It’s almost as if he feels he’s too good for his (from his perspective) dumb cabaret audiences. And, this being seventies West Central Scotland, there are far too many jibes at Protestants – a reminder that Scotland remains divided by its own institutionalised religious apartheid, and it makes uncomfortable listening nearly four decades later. I imagine most Scots under the age of forty would find Solo Concert as hip and hilarious as Beowulf.

This was never a problem with Boyce. Although, like Connolly, he is apt to crack himself up with his own wit, he has a bashful, self-deprecating air about him that removes such barriers. Religion is not an issue here, and although he takes a few mild pot shots at England, he is not particularly anti-anything; more importantly, he’s pro-Welsh. His delivery is not gruff and cross like Connolly’s; his light tenor often gives his voice a plaintive, near androgynous air (“Tick-et-less!” he exclaims delightedly near the beginning of “I Wandered Lonely”), and if that self-deprecation sometimes leads towards bending his voice to mask the occasional punchline, this is all part of his personality, and his audiences certainly get it. And him.

For this record reminds us that Boyce is utterly at one with his audience; each treats the other like their equal, and there is love rather than spitting content. He had been working the Welsh club circuit for years, and in late 1973 tried out on Opportunity Knocks, without success. Still, his stage reputation grew big enough for EMI to take a chance on him; the resultant album, Live At Treorchy, was an immense hit in Wales, and a word-of-mouth success elsewhere in Britain; although the album never placed higher than #21 in the national charts, it stayed there for fully eight months. One of its songs, “9-3,” celebrating a celebrated rugby victory by Llanelli against a touring All Blacks team, contained the line “we all had doctors’ papers,” i.e. the entire working class population had been signed off work by their doctors so they could go and see the match. Subversive stuff for 1974, and the spirit carried over to its sequel.

The cover is almost entirely a Where’s Wally?-type affair, drawn by “Gren” (“Cartoonist of the South Wales Echo"), and apart from a picture of Boyce himself, stern in his medical get-up and strongly resembling the young Danny Baker, it is all a cartoon of crowds swarming around and into the rugby ground, with numerous hidden celebrity cameos – mostly distinguished Welsh names of the period, but we also spotted Laurel and Hardy, Tommy Cooper, Batman and Robin, Harold Wilson and the Queen (and the fellow holding the giant leek is, I suspect, meant to be Boyce himself) – with humorous notices and banter, two speech bubbles indicating the first appearances in this tale of the future colloquialism “innit.” It’s all about getting one over on the powers that would be, in favour of the greater good.

Boyce clearly needs to prove nothing to this audience. His backing group – guitarist Neil Lewis, bassist John Luce and MD Jack Emblow on keyboards, accordion, etc. (with Boyce himself contributing guitar work) – set the scene with a furious sprint through “Sospan Fach,” Boyce’s adopted theme tune, which invites immediate clapping and sing-alongs. Then Boyce arrives on stage with his cheerful war cry of “Oggi oggi OGGI!” (Audience: “Oi! Oi! OI!”) and launches into a warm mixture of stand-up and songs.