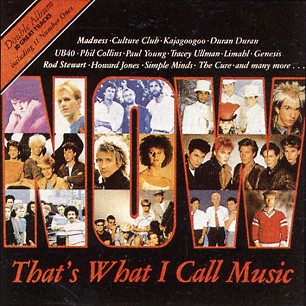

(#293: 17 December 1983, 4 weeks; 21 January 1984, 1

week)

Track listing: You Can’t Hurry Love (Phil Collins)/Is

There Something I Should Know (Duran Duran)/Red, Red Wine (UB40)/Only For Love

(Limahl)/Temptation (Heaven 17)/Give It Up (KC & The Sunshine Band)/Double

Dutch (Malcolm McLaren)/Total Eclipse Of The Heart (Bonnie Tyler)/Karma

Chameleon (Culture Club)/The Safety Dance (Men Without Hats)/Too Shy

(Kajagoogoo)/Moonlight Shadow (Mike Oldfield)/Down Under (Men At Work)/Hey You

(The Rock Steady Crew) (Rock Steady Crew)/Baby Jane (Rod Stewart)/Wherever I

Lay My Hat (That’s My Home) (Paul Young)/Candy Girl (New Edition)/Big Apple

(Kajagoogoo)/Let’s Stay Together (Tina Turner)/(Keep Feeling) Fascination

(Human League)/New Song (Howard Jones)/Please Don’t Make Me Cry (UB40)/Tonight

I Celebrate My Love (Peabo Bryson & Roberta Flack)/They Don’t Know (Tracey

Ullman)/Kissing With Confidence (Will Powers)/That’s All (Genesis)/The Love

Cats (The Cure)/Waterfront (Simple Minds)/The Sun And The Rain (Madness)/Victims

(Culture Club)

Looking at the track listing

for the forthcoming Now 87, I note

with some dismay that all of the hitherto unknown songs included have entered

yesterday’s midweek singles chart. This is not a new phenomenon with Now compilations and its continuation

indeed supplants my dismay with disquiet. It is as if the charts have been

meticulously plotted so that all of the untried and untested singles will debut

at precisely the right moment and hence make next week’s compilation look

fresher than fresh. It is as if pop music has been planned to death.

Listening to the first Now volume of all, I also note that we

have not really completed the circle begun by Raiders Of The Pop Charts. Instead of finishing where 1983 started,

with a thirty-track, TV-advertised double compilation album, it is quite

apparent that we have ended up somewhere entirely different; somewhere not

quite so shambolically comfortable, and somewhere a lot more disturbing and

possibly fatal.

Is that last sentence an

overstatement? The overall priority of the Starship Enterprise, you may

remember, was to observe history

rather than try to change or influence history. With the many

TV-advertised compilations featured in this tale between 1972 and 1983, the

overall picture is one of a slightly inchoate assemblage of cottage industries

and an agreeably sloppy attitude to compiling these collections; it really was

a case of working with what you could lease from whatever record companies

would be prepared to lease to you, finding unexpected connections and more than

occasionally throwing a very welcome curveball. Ronco, K-Tel and Arcade

compilations – not to mention things like Don’t

Walk – Boogie (a true ancestor of the Now

series) - were, broadly speaking, a mess, occasionally a hugely irritating

mess, but generally a rather surprisingly fertile one.

My suspicion is, however,

that with the dawning of the Now

franchise, we witness the beginning of a direct attempt to influence the course

of pop music, and maybe even how pop music is made or consumed. The first

volume was advertised with a painstakingly irreverent voiceover by one of its featured artists, Tracey Ullman; the subtext was that this was not bargain

basement, available at Woolworths and Rumbelows K-Tel time.

The overall aim – or one of

them – seems to have been to put the house of the compilation album in order.

Although essentially a joint venture between EMI and Virgin, it was Virgin

Records who came up with the initial idea (and negotiations for the concept

involved Richard Branson himself). The album was advertised by a curious logo;

a beaming pig listening over a garden fence to a chicken singing, and

proclaiming “Now that’s what I call music!” In fact this was originally a 1920s

advertisement for Danish bacon, but Branson bought a poster of it as a present

for Virgin Records’ then managing director (and Branson’s cousin): “He was

notoriously grumpy before breakfast and loved his eggs in the morning,”

observed Branson, “so I bought him the poster, framed it and had it hung behind

his desk!"

Following negotiations,

Virgin managed to persuade EMI to come on board with the venture – this was the

first time major labels had collaborated on such a large project. Some hits

were then leased from CBS, WEA, Polydor, Island and Stiff, but none from

Arista, RCA, MCA, Chrysalis, A&M or Phonogram. There was still quite a lot

of scepticism as to whether the Now

project would work, and some unrest about whether, if popular, the album would

hinder the sales of artists’ own albums – one may view the delayed entrance of

several major acts on Now II as

having waited for the waters to be tested before becoming involved.

But the first Now album was an immediate success; it

sold 900,000 copies over the Christmas/New Year period and more or less rendered

the TV-dependent labels redundant overnight. Packaged immaculately – some might

say suffocatingly – Now 1 seemed to

promise proper quality; no sloppy covers pasted together in five minutes, no

filler, full, unedited 45 versions. It appeared to legitimise the enterprise of

multi-artist compilations, push them into growing up.

And yet listening to it is

such a cold, deadening experience. Overwhelmingly, despite the presence of

eleven of the eighteen singles to make number one during 1983, it is far too safe

a selection of hits, and the absentees imply that we are dealing with the

second tier of pop stars, or possibly tier 1a. For the record, neither 1983’s

first number one nor its last is included. The first was a hangover from 1982,

“Save Your Love” by Renée and Renato, a calamitous confirmation of what happens

when camp is taken too seriously, or not seriously enough (it is the missing

link between “Welcome Home” and “Barcelona”), and it says something about the

nascent Now brand that this would

have seemed out of place on any Now

album (though would have fitted without complaint onto any K-Tel or Ronco

record). The last – another unanticipated novelty – was released too late for

inclusion (and wrongfooted certain grave assumptions about Now 1) and appears on Now II.

Of the remaining five missing chart-toppers, “Billie Jean,” “Let’s Dance,”

“True” and “Every Breath You Take” have already been written about in the

context of their parent albums (and their absence here implies that they are

just too big to go on Now, since

Bowie was, at the time, an EMI act). This means that the one remaining absent

number one, Billy Joel’s “Uptown Girl,” will simply not be written about here

directly. That, I am sure you will agree, is a tragedy beyond comprehension.

But how can you have a 1983

greatest hits album without “Blue Monday” or anything by Michael Jackson? How

much better would any of the C90 cassettes you and I would have filled with our

versions of 1983 music have been? And why so safe a track listing – get past

Simple Minds, plus atypical songs by Genesis and The Cure, and there is no rock

as such – Big Country, U2, Echo and the Bunnymen, even EMI recording artists

Iron Maiden – all for the boys, all absent. In fact the record seems to have

been scrupulously assembled so as not to frighten or disturb, or even

momentarily stir, anyone who buys it or listens to it; “This Is Not A Love

Song” by Public Image Ltd, released on Virgin and beyond dispute one of 1983’s

greatest singles, was a much bigger hit than many of the songs included here,

but you will search for it on this record in vain.

Actually the TV-advertised

labels were not quite down the dumper; the late 1983 charts also included three

BOGOF compilations; The Hit Squad

(Chart-Tracking & Nightclubbing) (Ronco), Superchart ’83 (Telstar) and, a revisit from 1981, Chart Hits ’83 (K-Tel). There is

necessarily some overlap between this trio, but they do provide a fuller and

less predictable picture of the year’s hit music; if you’re looking at the Now 1 track listing and wondering where

such and such a song is, odds are that they are on at least one of these three.

But it was a losing battle; in the following year, 1984, Ronco filed for

bankruptcy.

In other words, Now 1 was the future. But what kind of

future was it trying to create? Remember what I said about the series trying to

influence history. At the time of this record’s release, several of its tracks

were climbing the chart as singles, and it’s possible that the surprising

underperformance of hits like “Waterfront” (peak position #13; not remotely

indicative of the song’s true popularity) and “That’s All” (#16) is directly

ascribable to their inclusion here. But the record’s attempted coup de theatre was to conclude with

“Victims”; the assumption being that, having begun with the year’s first “new”

number one, the record would close with the final one. It didn’t work, partly

because of Now 1 itself and partly

because Colour By Numbers was still a

hugely popular, big-selling album, but also in part because, as a single,

“Victims” was too complex and involving a song to cross over as effortlessly as

the knowing bubblegum of “Karma Chameleon”; there are no real hooks, no easy

emotional compromise. It is just too disturbing for that (it peaked in third

place in the Christmas singles chart).

And, if pop can sometimes,

at its best, prove really disturbing, I also have to say that I cannot imagine

a similar enterprise being undertaken even twelve months previously. Leasing

problems notwithstanding, what would a Now

That’s What I Call 1982 have looked like (and before any smart alecks come

on board to point it out, I am fully aware that ten year-specific Now Eighties collections were released

many years later, and no, I don’t think the 1982 album would have looked like

that at the time)? My feeling is that

the pop of 1982 was overall too radical, too disturbing, to act as a comfort

blanket for casual supermarket consumers, and that in itself may tell us how

things had perhaps lowered slightly in terms of the horizons of the following

year’s pop. Did the pig really represent the lazy, sated consumer fully

prepared to pay money to buy a new packaging of what was already available;

indeed, when some of its content was still new? Or did the pig represent the

bloated, indulgent music industry who’d be perfectly happy to sell the public

records of a chicken clucking if they took off?

Phil Collins/Genesis

An early indicator of how

readily "adventurous" musicians from the seventies were prepared to

dress up and dumb down for the unforgiven eighties. The song's imperious beat

and encouraging catchy tune, as demonstrated in the Supremes' 1966 top three

original, hide a near-suicidal lyric: "But how many heartaches must I

stand/Before I find a love to let me live again?" These are words crying

out for Orbison at his most tormented, yet Diana Ross at her perkiest is

strangely but equally convincing at conveying the song's underlying

desperation.

Collins' cover, which in

itself is faithfully facsimilied in the mode of a reproduction antique – his

vocals aside, the recording might as well have been taken from one of those Hot Hits make-do-and-mend albums - was

the only substantial hit single from his second solo album, Hello, I Must Be Going!, by some

distance the weakest-selling of his '80s tetralogy, full of interchangeable

whining ballads about his first divorce. They do not include songs entitled

“You Can’t Take My TV” or “Why I Pay You To Go Out With Fancyman (Why I Not

Break His Jaw)?,” despite what the eximious Comstock Carabinieri claimed, but

it’s a close call. It's also telling that virtually all of his cover versions

come from an idealised 1966 - "Tomorrow Never Knows" on Face Value, "A Groovy Kind Of

Love" from Buster - but

unfortunately whatever minor merit his "You Can't Hurry Love" might

have possessed is utterly nullified by its rather creepy video featuring

multiple besuited Collinses, unflatteringly filmed on VT, performing a Blues

Brothers tribute, as if the song were just a piece of laughable fluff from his

schoolboy years to be sent up. As for “That’s All,” The Cure do a better

Beatles on “The Love Cats.”

Duran Duran

“PLEASE PLEASE TELL ME NOW!” they demand, in the manner of anxiously

psychotic hostage takers. The “Look Of Love”-derived intro heralded an attempt

at adding a harder, tougher edge to Duran Duran’s pop – le Bon’s “I KNOW you’re watching me” and “DON’T SAY you’re easy on me” warned

listeners that he really was not to be messed around with (actually he sounds

not a million miles away from that other renegade Brumrocker Ozzy Osbourne).

Hence when le Bon tells of “jungle drums” we receive booming “Poison Arrow”

echoes of drum. It’s pretty clear that this is a transitional record and also

why it didn’t get included on Seven And

The Ragged Tiger; musically the most interesting ingredient is John

Taylor’s bass (particularly in the fadeout, under le Bon’s “Every time it

passes by”), and while producer Alex Sadkin is always aware of the value of

space and silence, and a harmonica strays in from an old career in an old town

during the instrumental break (are we really as big as the Beatles?), this is a

relatively disappointing piece of work; the ingredients to enable development

of their music are all present, but are, at this point, still only perhaps

three-quarters baked.

UB40/Bonnie Tyler/Paul Young

One central problem with the

Now series, apart from making great

pop sound dull, is that sometimes 45 edits are no longer enough. Some songs are

now benefiting from their full album length, such that any single edit is like

looking at just one corner of a painting rather than the whole thing; otherwise

they run the danger of sounding emotionally constipated. The edit of “Total

Eclipse” here is (pace what I said

above) different from the edit on the original 45 and still unsatisfactory.

Then again, “Please Don’t Make Me Cry” is unedited, if a wholly unnecessary

inclusion. A very long way indeed from “So Here I Am.”

But those sleigh bells on “Total

Eclipse.” One is never too far away from the Beach Boys, or indeed from Dennis

Wilson, who slipped into the blue Pacific Ocean, never to resurface, on 28

December 1983.

As regards Paul Young’s “Wherever

I Lay My Hat,” see also Scott Walker’s “Orpheus” from 1966.

Kajagoogoo/Limahl

“Johnnie Ray!” exclaimed

Lena as we endured “Only For Love” (“And! Ew-YOU! RrrrrrRECOGNISE!”). Or

perhaps a glossier variant on Chris Andrews, whose “Yesterday Man” was

re-covered by Robert Wyatt on a very different Virgin Records compilation album

in 1975. But one of the major failings of Now

1 is the inclusion of three songs by Kajagoogoo and/or Limahl. Some might

say that was five more than was absolutely necessary.

Kajagoogoo were EMI's

"priority new act" for 1983. They achieved some useful publicity

touring as support to Duran Duran, and Nick Rhodes even co-produced their first

single. Their profile was heightened further by an appearance on the Channel 4

series The Other Side Of The Tracks,

presented by an expatriate American broadcaster who is currently under a legal

cloud, and who was then the partner of lead singer Limahl - just before the

Christmas of 1982.

Everything about "Too

Shy" betrays the slide rule. It is a ghastly melange of absolute

misunderstanding of New Pop; as if the swooning entrance of the keyboards

allied to a burbling, harmonically ambiguous bassline could in itself conjure

up Level 42, or Japan. When Limahl enters for the first verse, it becomes

worse; a tortuous Lexicon Of Love

parody ("Try a little harder" with sub-sub-sub-Anne Dudley piano)

swiftly followed by dangling Tin Drum/New Gold Dream angles of warbling synth

over which Limahl coos "Move a little closer" in the manner of Cheggers Plays Pop host Keith Chegwin,

before we reach the chorus which fully reveals Kajagoogoo as the dull,

Jamiroquai-presaging jazz-funk drones they secretly always wanted to be - and

when Limahl huffily walked out, or was pushed (depending on whom you ask), some

six months later, they indulged their sub-Shakatak fantasies freely (“Big

Apple,” which set new standards in flaccidity, both musically and lyrically, is

perhaps the worst song about New York ever written, from the perspective of

people who sound as though they had travelled no further west than Hounslow).

The song seems to be about sexual timidity, but faced with Limahl, one is

scarcely surprised by his Other's reluctance to "dilate." "Too

Shy," however, dilates New Pop to the point of nullity.

There was an album – White Feathers, which peaked at #5 at

the end of April, and which, despite including songs entitled “Ergonomics” and

“This Car Is Fast” – and two other hit singles that are rather more disturbing

than “Too Shy” (“Ooh To Be Ah” might still be one of the most abstract things

ever to make our top ten; play against, say, Gabi Delgado’s “History Of A Kiss”

and see the connections, while “Hang On Now” is a downbeat ballad sung as

though its singer were hanging onto the edge of the world with a turquoise

fingernail) – is ultimately no more than placid jazz-funk, even if in Icelandic

terms it might be a missing link between Mezzoforte and Björk. I mean,

“Magician Man.” Whereas Limahl’s first solo effort (which peaked at an

unsurprisingly low #16) is not even interestingly random, like a Dadaist jigsaw

puzzle, but merely a ghastly cut-and-paste of 1983 pop elements, none of which

fits with each other. As well as equally ghastly and obligatory soulful,

passionate and honest backing singers. Honest about what?

Heaven 17/Human League/Tina Turner

From the first second of

“Temptation,” you are never in doubt that, unlike Limahl, Heaven 17 know how to

structure a great pop record, and they also know that without conflict and

pain, there really wouldn’t be much pop music, of any stripe, left. If “Let Me

Go” had given notice that the dream wasn’t working, or even coming true, then The Luxury Gap from its cover inwards

set about demolishing illusion. The knowledge that it’s all bullshit, that you

can travel the world, go crazy with plastic and before day is done you still

have to get back, get home, to desolate, semi-derelict Sheffield – such things

power the polite screams of “Key To The World “(“I’m Mister Obsolete –

DELETE!,” complete with the ironically opulent Earth, Wind and Fire horn

section) or “Crushed By The Wheels Of Industry,” or the quietened tragedies of

“Come Live With Me” (the song Rod Stewart never sang, but should have done) or

the closing “The Best Kept Secret” which sees Glenn Gregory staring out onto an

ocean of nothingness which will evidently take forever to fade.

“Temptation” is angry,

righteous, arranged with maximal ingenuity by BEF and sometime AMM accomplice

John Barker, with a continued, upward, creeping angle of progress between

topline chords and underscore rhythm which anticipates what Calvin Harris would

do on 18 Months. It is sinister yet

ultimately liberating, thanks to the explosive co-lead vocal of NYJO graduate

Carol Kenyon.

Both Heaven 17 and the Human

League peaked at #2 behind “True” in consecutive weeks; Top Of The Pops proved a challenge. But “Fascination,” Melody Maker’s single of the year for

1983, was the last thing that Phil Oakey’s League did with Martin Rushent, and

overall – although there was no telling at the time – the record (still

credited to “Human League Red”) serves as a fond farewell to the association,

with everybody in the group taking a vocal turn, and Jo Callis’ wobbly

guitar-processed-via-synth riff sounds like the missing link between “Magical

Mystery Tour” and “Only Shallow.” Meanwhile, Oakey’s deep “hey, hey, hey, HEY”

is reminiscent of Larry Graham with Sly and the Family Stone.

But then there is Tina

Turner, returned like the grown-up co-protagonist of “Temptation,” and these

days she had seen, and how they bled their way slowly into how she sang “Let’s

Stay Together” – is my memory fallible, or was the original single credited to

“B.E.F. Presents Tina Turner” (it might have been “Ball Of Confusion” from

1982)? In any event, it was the Heaven 17 fanbase who got it into the Top 40, but

then perhaps an older demographic helped elevate it into the Top Ten; absent

from the charts for a decade, and perhaps from the world from as nearly as long

a time, here she was; alive, and in pain, and euphoric, the B.E.F. voices

gently ushering her into centre stage, and for once the old times were

justified.

KC & The Sunshine Band

Lena commented that “Give It

Up” might well have been the “Get Lucky” of its age and I would agree with

this. Long, hot summer – no, Weller’s nowhere to be seen here – and a number

one song inhabiting that nice middle place where everything just works. Also

“Give It Up” was the year’s only number one single without an accompanying

video (N.B.: there was a VHS companion to this album which included the

otherwise Now-avoiding “I.O.U.” by

Freeez and “Never Never” by the Assembly).

The record was an unexpected

and brief but highly welcome resurgence of the Miami Sound. Only its discreet

synth marks out “Give It Up” as having been recorded in 1982 rather than 1974,

and that’s no bad thing. While “That’s The Way (I Like It)” remains KC’s best

record because of its underlying sense of approaching menace, “Give It Up” is

busily arranged but basically straightforward three-chord bubblegum disco with

a terrific good humour which is admirably happy to remain as such. An

anachronism in the land of “Just Be Good To Me” and “Hey You (The Rock Steady

Crew),” perhaps, but a contented one.

Malcolm McLaren

Worthiness is not the same

thing as worth. To seize a music, take it to pieces, expose it to its aesthetic

polar opposite and thereby (hopefully) refresh it is not a task to which the

adjective "worthy" should be applied. There are places for reverence

and respect as long as you don't let them block your future. I could spend the

rest of my life revering Spencer's Resurrection

at Cookham but simultaneously realise and adore the pelvis-driven

imaginings which give that masterpiece its multiple puncta.

As with World Music. If

music is truly to be of the world then it must by definition be exposed to

"impure" things, it must be acknowledged that the music itself is

probably "impure" to begin with. It cannot be adopted or handled with

dainty fingers, nervously examining their adrenalin reserves to ensure that

they contain adequate nullifying agents of respect. Otherwise any World Music

is all middle-distance, respectful, designed never to derange. More of a lead should

have been taken from Malcolm McLaren and Trevor Horn.

It is deliberate that, with

the Duck Rock project, McLaren set

out to combat and nullify what he viewed to be the sterile blandness of New

Pop. And how better to attack than to employ its chief architect, Trevor Horn,

to arrange and produce? McLaren said he wanted Horn to obtain some

"bollocks" in his work, get "a bit of the rough, the

spontaneous" into his meticulous productions. It is therefore doubly

ironic that Duck Rock is one of the

most seamlessly, microscopically put-together things which Horn ever did.

How did they approach this?

It was McLaren's ceaseless strivings for a new punk, and his moderately keen

ear for developments. He was in America while hip-hop and electro went

overground with Flash and Bambaataa, witnessed with amazement kids breakdancing

to a modified "Trans-Europe Express," scratching up records like John

Cage with a good drummer (a disciple of Karel Appel's COBRA group/philosophy as

well as of Debord, McLaren instinctively knew how to insert the art into this

sort of thing). His ears wandered vaguely in the direction of Africa,

specifically in view of Bambaataa's Zulu Nation and any connections which

McLaren could discern (Nigeria's King Sunny Ade and Senegal's Youssou N'Dour

had yet to break overground, though the former's Synchro System was, usefully, a minor UK hit at around the time of Duck Rock's release, while the fatally

less mischievous Laswell got to N'Dour first). His wits further led him to

discern a vague (probably imagined) link between the square dances of the white

South and the hip hop culture of the black North - apart from their both being

ritual occasions to allow participants to somehow become more

"themselves" - the same idea which, of course, prompted Punk into

existence. How to marry all of this up?

McLaren and Horn did some

field trips to NYC, Tennessee and the South African townships, made some

recordings and then returned to London to knock them into shape with what was

eventually to become the Art of Noise (indeed, the latter's epoch-beginning Into Battle EP largely originated from Duck Rock outtakes) with some help from

Thomas Dolby. Significantly, from NYC, they employed the DJ duo The World's

Famous Supreme Team to act as a kind of Greek chorus for the album, turning it

into one of their then legendary late night/early morning radio shows.

It's hard to visualise just

how radical the first single from the album "Buffalo Gals" seemed

when it came right at the death of 1982, right when certain careerist ambulance

chasers seemed determined to strip New Pop of all its mischief and sensuality.

And how appropriate that both McLaren and Horn should signify a way out. Radio

One played it; and their DJs sounded completely baffled but, to their credit,

they knew that this was something new and correctly predicted that it would be

a gigantic hit. True, to those long familiar with things like Grandmaster

Flash's "Adventures on the Wheels of Steel" (which just missed the UK

Top 75 about a year previously), this was not exactly something unprecedented,

although one could argue that what McLaren and Horn did with it was

unprecedented. Certainly square dance cut-ups were not yet on the Zululand

template, although downtown Double Dee and Steinski were simultaneously busy

preparing their likewise groundbreaking "Lessons." For the other big

hit off the album, "Double Dutch," McLaren reversed the template,

getting Zulu singers to exalt the praises of NYC skipping contests.

The album itself remains

eminently playable. Though the Supreme Team's patter is now a stock template for

Radio 1/Kiss DJs, it sounded fresh and spontaneous at the time, sounded like an

injection of (s)punk into the barrenness in which post-New Pop pop had marooned

itself. And McLaren let no stones lie in his "world tour." From the

near-holy murmurings of the introduction "Obatala" effortlessly into

the welcoming Supreme Team ("leave your guns at home! Tell me Shirl, how

do you manage to stay up until four o'clock in the morning to listen to our

show??!?") and the killer opening sequence of "Buffalo Gals," "Double

Dutch" and "Merengue," this is a grin-inducing record. On the

latter, six clear years before the Lambada came to public prominence, McLaren

gleefully romps through the salsa-meets-kwela-meets-Charlie Haden's Liberation

Music Orchestra like a postmodern Bruce Forsyth, excitedly intoning lines like

"nice little cemetarios will be waiting for you!" Even the fact that

McLaren's delivery (especially on "Double Dutch") recalls no one so

much as the late Harry Corbett of Sooty the Bear fame somehow lends even more

humanity and mischief to this record.

And what about "Punk It

Up"? In his sleevenotes, McLaren recalls the glee and enthusiasm with

which the Zulus entertained his stories about the Sex Pistols, and how enlivening

and joyous it is to hear the Zulus singing, "I'm a Sex Pistol man" to

top-notch Afrobeat. This seeming disrespect for "other musics" (sics)

actually betrays a greater and deeper respect for them than mere Xeroxing and

blanding out. The whole thing continues in similar (if slightly more

contemplative and ritualistic) mood on side two before bowing out with

"Duck For The Oyster," a straightfaced square dance for fiddles and

scratch DJs where McLaren manfully fuses both mutually hating though ultimately

alike extremes together. Note the parting cry of "Promenade you know

where/AND I DON'T CARE" where he performs the final bonding ceremony with

Punk and thereby regenerates it.

A shame that no room could

be found on the CD for perhaps McLaren and the Supreme Team's greatest moment,

"D'Ya Like Scratchin'?" (the B-side of the 12-inch of

"Soweto") where the Team's especially demented scratching interacts

with proto-Art of Noise beats to almost hysterical levels until McLaren strides

in with a straight hoedown version of "Red River Valley" (cf.

Scooter's "Fuck the Millennium" to see how this spirit remains

propagated even into the present century). But this is a joyous record which

superficially doesn't give a fuck but deep down its fuck is much more sincerely

given than any "worthy" or "respectful" people I could

mention could really offer. Liz Phair quoted “Double Dutch” in her song “Whip-Smart,”

while Paul Simon, with whose “The Late Great Johnny Ace” we could close down

1983, was sufficiently intrigued by the record to begin a controversial

adventure of his own.

Culture Club/Men At Work

Say something once, why say

it again?

Men Without Hats

A classic example of an act

wrongfooting its audience with its videos – although the medieval undertow of “The

Safety Dance” was really always evident. They were from Montreal, they came,

they impacted and they went back into the rest of the world.

Mike Oldfield

A decade after Tubular Bells set the whole thing going,

was it deliberate, or a nice accident, that Virgin’s original star should

reappear on this record? On TOTP he

looked ecstatic, clean-shaven and grinning, perhaps relieved at no longer

having to share a chart with Paul Nicholas or David Soul, accompanying Maggie

Reilly, erstwhile singer with Glasgow white soul band Cado Belle, with guitars

which at times border on the hysterical. All in keeping with a song whose

subject matter is the assassination of John Lennon, that other 1980 ghost whom

New Pop can’t quite forget.

The Rock Steady Crew

“DIGITAL” beeped the voice,

repeatedly, and top B-boy producer Stephen Hague, presumably with Duck Rock on his mind, set about

recording this fantastic piece of avant-bubblegum (although it is really “Hang

On Sloopy” plus “Looking For The Perfect Beat”). Like “I Can See For Miles,”

there is continued build-up (the live turntable scratching = Keith Moon’s cymbals)

but no climax or release. Pop, this is your smiling future. At least until you

see the video and watch with an increasing rictus grin as the second half turns

into a display of American military weaponry. World, this must not be your unsmiling

future. But the song was sampled by De La Soul (on “Cool Breeze On The Rocks”)

and the nod to Numan at fadeout suggests that somebody else will have the last

laugh.

Rod Stewart

All this new-looking design;

all these old-looking names. If someone had time-travelled from 1976 to 1983

they’d still recognise Genesis, Mike Oldfield, Tina Turner, Roberta Flack,

Bonnie Tyler, KC & The Sunshine Band. If they were really hip they’d

remember that Malcolm McLaren was the Pistols’ manager.

And of course Rod, always

bloody Rod, haven’t seen you since the seventies Rod. "The situation ain't

all that new," croaks Rod, and indeed it isn't; the

brought-you-up-from-nothing plot is borrowed from "Don't You Want Me?,"

the rhythm from Eddy Grant and the resignedly exasperated tone from

"Maggie May." A dozen years on from the latter and now it's Rod's

turn to tell his ungrateful paramour to sling her hook, though the line

"I've said goodbye so many times" indicates that the problem is not

one of the semi-hapless Jane's making.

Soaring to number one on the

back of a bizarre WEA promotional campaign which included a free beach ball

with every copy of the single - oddly this offer was only available at chart

return shops - "Baby Jane" is Rod's sixth, and to date last, number

one single, and it is the most airless. Revisiting this most purposely forlorn

of 1983 hit singles, the overwhelming sensation is one of nullification;

despite the presence of Tom Dowd as co-producer (with Rod), this is yet another

"big" and seamless production, treble-heavy and metronomically

precise, such that no art can hope to breathe or thrive within its

consumer-flattering/suffocating bubble-packed surface. However, the bluff

"When I Fall In Love" citation does provide an early indication of

Rod's eventual (though not permanent) mutation into a hoarse-faced

granny-pleasing MoR crooner. Cheryl Cole’s birth song; it’s enough to make me

feel sorry for her.

New Edition

The pre-eminent pop producer

in 1983 was not Trevor Horn - at least, not the pre-ZTT Horn - but the team of

Arthur Baker and John Robie. In striking contrast to the maximalism of ABC and

Dollar records, and with a keener ear to the urban ground, Baker and Robie

stripped their productions of anything approaching lushness in favour of skittish,

deeper beats with a staccato rather than ambulatory perspective applied. There

is evidence that the noticeably tougher Horn who emerged with things like Duck Rock, Art of Noise and "Owner

Of A Lonely Heart" from mid-1983 onwards was provoked into substantial

rethought after experiencing the impact of Baker and Robie's steely futurism.

Bambaataa's immensely important "Looking For The Perfect Beat" was

the first single to feature digital rather than manual sampling. Records like

Freeez's "I.O.U." and Robie's astonishing double whammy of C-Bank's

"One More Shot" and Jenny Burton's "Remember What You Like"

are beyond-Futurist cut-ups of notions of "song" and

"voice"; it is a wonder how, on the latter two singles, Burton

manages to retain her elegance and grace while being assaulted from all sides

by smashing glass, gunfire, car horns and Corbusier-proportioned beats. And of

course there was "Blue Monday," the point where all pop music meets,

simultaneously the beginning, suspension and end of time, the supreme

seven-and-a-half minute denial of 1983's ruination (because the song is about a

ruination) and a record whose importance casts a yellowing shadow on the

subsequent quarter-century of pop, a record so vital yet accidental that Baker

left his name off the label credits but later owned up to having produced it

(Robie is credited with the mix).

But there were also minor

ambitions to do a Motown; see the Andromeda

Strain Four Tops of Planet Patrol's "Play At Your Own Risk" and

"Cheap Thrills" (although Planet Patrol’s eponymous album remains a

marvel), and most clearly and depressingly evident in "Candy Girl,"

strictly speaking a Maurice Starr and Michael Jonzun conception, but produced

by Baker and Robie. The song is little more than an electro update of

"ABC," Ralph Tresvant was never going to be another Michael Jackson,

Bobby Brown's rapping was annoying even at that early stage, and next to the

unforced naturalness of Musical Youth it all still seems more than a little

contrived, and probably in an unpleasant sense. This underlines the ultimate

failure of Now 1; so we couldn’t get

Michael Jackson, the biggest pop star on the planet, but here’s somebody who

sounds like he USED to sound. And somebody else in the background who will grow

up to be somebody extremely unpleasant. What was that about a Georgian market square,

and hell?

Howard Jones/Simple Minds

To be written about in the

near future, but not here. For now there is Bob Marley’s “Emancipate yourself

from mental slavery” and there is “Throw off your mental chains.”

Peabo Bryson & Roberta Flack

Side three was evidently

meant to be the “adult” side, as it closes with UB40’s “Please Don’t Make Me

Sleep” followed by this 1975 snooze of a Mathis

Collection duet. But the sequencing is beyond awry and the hoped-for

demographic much too hopelessly wide. Did anybody like Peabo Bryson AND The

Cure? And yet for one week this outsold “Karma Chameleon.” Where’s “Islands In

The Stream” when you need it?

Tracey Ullman

The Kirsty MacColl-ness. The

punctum pause: “Ba-a-by-y!” He’s bad, but I love him: see “Papa Don’t Preach.”

Potential sequel to this song: “Fairytale Of New York.” Did Amy Winehouse hear

this record as an infant? It plays like a happy Amy song, complete with the he’s-bad-BUT

trademark. More ahead of its time than you imagine. The only woman on the

cover, in the centre of a field of men, two of whom appear twice.

Will Powers

It doesn’t say very much

about any newness relating to Now 1

that its most outré moment is

provided by, of all people, Lynn Goldsmith, with her musical chums, nearly all

of whom were around before punk. Terrific in a Tom Tom Club kind of way – it could

so easily have fallen over into the Meri Wilson side of that particular fence –

and Carly Simon might not have sounded better or more alive than here.

The Cure

I wish I could provide Cap’n

Bob with a more positive welcome to TPL

but The Cure essentially mucking around with jazz and psychedelia has been so

eroded by three decades of radio overplay that it’s completely lost its

mischief. No, Pornography was as far

as “that” Cure could ever have gone without exploding. But “Let’s Go To Bed”

was better pop and none of the Banshees hits or spinoffs (“Dear Prudence,” The

Creatures, The Glove) bothers to put in an appearance here. To the record’s

loss.

Madness

Their last top ten hit in

their original lifetime, and hardly heard now; it plays like a miserablist

dilution of 1982’s “Primrose Hill,” and only David Bedford’s strings lift the

song out of the morass. Suggs sings like Robert Wyatt hidden behind a muffler, “Wings

Of A Dove,” though incongruously jaunty (it made number two but sounded as

though the band were beginning to make records to please NME writers), was a bigger hit, no useful sense of liberation or

catharsis is communicated, and ultimately we are left with a…

…Hall Of Mirrors

A sense of no risk being

taken. A sense of the record not being ambitious, or brave, enough. A “grazing

experience” as Lena put it.

But there is more, and it is

sinister; I think that the arrival and success of the Now brand constituted the first nail in the coffin of what is

generally regarded as the pop single. Think, even, about that “I” in “Now That’s

What I Call Music”; who is this “I”?

Who’s doing the deciding, the dictating? It might not be as threatening as the “we”

of today – “Why we all love Breaking Bad”

when one has not even SEEN Breaking Bad

– but it was a way for the old, conservative music industry to get back in,

having worked New Pop out, and nipping any genuine newness in the bud. It would

affect the way people regarded the single – if they are all handily collected,

why bother with singles? – and, worse, alter the way in which pop was

conceived, listened to, watched and sold. Soon (in 1983 terms) there will come

the time when worried record companies will begin to make records in the hope

that they will end up on a Now

compilation, and a generation before the internet makes its full impact, the

consumers will gradually disengage themselves from the form. Before long, TPL will consist of little other than

these records, these treated logs, these doctored journals, and solidification

and morbidity will set in.

NOW, the British music

industry knows exactly what the hell is going on in their own world, and will

be damned if they will give it somebody else, somebody new and untested, or an

established artist whose career plan won’t particularly be advanced by

inclusion on these records. Thatcher had won again in July 1983. Everything,

and everybody, was happy. Don’t complain. Don’t DARE complain. Be the worst you can be.

Like I said, Now is the end of something, and this is

the fulsome picture of the hell that has now arrived; people pretending to be

happy when their souls and their homes have been stolen away, the school choir

unity of too many charity records to come, the desecration of gospel that will

culminate in Cowell, the central assembly point for people who don’t want

subtext, excitement or outrage – or even mild difference – but shiny conveyor

belt shite that will fit in the checkout with the Brillo pads and Johnson’s air

fresheners.

This music was better when I

was nineteen.

But, these days we can no

longer see.